Dangers of Mold - by Pete Fowler. Published by Window and Door Magazine in 2003

Lack of accepted standards and a large number of variables mean costs can escalate quickly

You’ve probably seen it on TV, and read about it in newspapers and magazines. You can find more information about it on the Internet than you could ever read, even if you quit your job to do it. For window and door manufacturers, distributors, dealers and installers, or for a business that is related in any way to building construction, real estate or insurance, mold is a scary subject.

In 1999, mold claims only came along with a small percentage of the projects I worked on as a construction consultant involved with insurance claims and litigation issues. Now claims without allegations of mold are equally rare, in Southern California at least. Have the natural or built environments changed, causing a spike in the amount of mold growing in California, or is the interest in mold due to changes in the insurance and legal environments?

The health issues that have been widely reported in the media are a real concern, but the problems do not stop there. The “dangers of mold” also include: expenses for expert inspection and testing; remediation; alternative living expenses; legal costs; business interruption; insurance coverage with skyrocketing costs or a lack of availability; bad publicity; the ambiguity in all of the above due to a lack of standards; and more.

There is an enormous volume of confusing and contradictory information available on the topic of mold and a rapidly growing population of folks claiming to be “mold experts.” We’ve all heard the horror stories, but what do you need to know as a window or door manufacturer, distributor, dealer or installer suddenly drawn into a mold-related problem? This article is designed to help you cut through the haze, give you an idea of who you should have on your team, and tell you where to find reliable information. With a little background, you’ll be able to tell if the “experts” you encounter are giving you the straight story or using the complexity and media hype as scare tactics.

What is Mold?

Let’s start with the basics: mold is any form of multi-cellular fungi that live on plant or animal (organic) matter. There are more than a million different fungal species in the world. To grow, mold requires food, moisture and time, and can flourish in temperatures between 40 and 100 degrees Fahrenheit. Even in the absence of ideal conditions, mold can lie dormant for years and “re-activate” if living conditions improve.

“Toxic molds,” a term that has been rejected by the American Industrial Hygiene Association and many experts, are those that can produce mycotoxins, and include aspergillus, penicillium, stachybotrys and others. These are the molds that you hear about on television, where some experts say they can cause severe and permanent damage to humans.

How Does it Affect Us?

Health effects of mold are at the heart of the debate. It is agreed that all molds can cause “allergic-type” reactions in humans, such as coughing, wheezing, sneezing, irritated eyes and throat, and runny nose. More severe effects may include flu-like symptoms such as fever, fatigue, respiratory dysfunction, excessive regular nosebleeds, dizziness, headaches, diarrhea, vomiting and impaired or altered immune function. Reports of these more severe symptoms are very rare, and they only occur in a small percentage of the population. Other frightening claims include a loss of balance, cognitive impairment, memory loss, pulmonary hemorrhage, liver damage and near blindness, some of which are claimed to be permanent.

Various scientific groups and agencies are in the midst of research to identify any possible link between mold exposure and permanent damage to humans, but there is no certainty widely agreed upon at this time. Most recently, the American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine published a position statement concluding that current evidence does not support the proposition that human health has been adversely affected by inhaled mycotoxins in home, school or office environments.

There are risks, but we don’t even know how much mold is too much. There are no standards yet for acceptable exposure. There are also no tests for verifying human exposure to mold, in contrast to, for example, lead and asbestos, where physically testing the victim can prove exposure. There is, however, agreement as to who among us is most vulnerable to the effects of mold exposure: infants, children six years and younger, pregnant women, the elderly, asthmatics, allergic individuals and immunecompromised individuals, including those with HIV.

While the health effects are not fully understood, one of the clear dangers of mold for companies in the building industry is the ambiguity due to a lack of definitive standards. The ambiguity is reduced when a genuinely qualified professional assesses a contaminated site and makes recommendations based on professional judgment. But it can get ugly when another party disagrees with that assessment, because the differences in remediation costs can vary wildly and there is often a question of who pays the bills. These differences of opinion occur more often now that attorneys and “Johnny-come-lately” mold experts are an increasingly common part of the equation.

The experts who are brought into a mold case may point to a wide variety of sources for their claims, but the most commonly used guidelines come from the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, hereafter called “NYC,” the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Texas Department of Health and Texas Department of Insurance, the American Industrial Hygiene Association and the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists. The information provided in this article comes from one or more of these sources. To provide some background for companies that may face mold issues, we’ll look at some of the processes used to determine whether mold is a problem, and if so, what needs to be done to address it.

Inspection and Testing

Visual inspection is the most important initial step in assessing a situation. The amount of mold observed determines the extent of the remediation, the level of containment and the type of personal protective equipment required for workers. There are two reasons for the inspection and testing:

➣ To determine the source of the moisture and collect enough information so a repair plan can be developed to make sure the problem does not recur

➣ To determine the extent of contamination so a method of containment and remediation can be developed to safely rid the building of mold.

Bulk or surface sampling is performed by using cellophane tape or a cotton swab to collect the mold. The sample is later analyzed in a laboratory by microscopic (visual) observation. Various authorities note that identification of the spores or colonies requires considerable expertise. The NYC standard maintains that bulk or surface sampling is not required to undertake remediation, and that visual observation is adequate for assessment.

When the quantitative analysis of “how much mold is here” begins, the heart of the difficulty is found: Unlike lead or asbestos, the existence of mold does not have a “yes” or “no” answer. There are always some molds in the indoor environment. We can easily understand that, all things being equal, mold counts in a well-kept home could be less than mold counts of inferior housekeepers. This is just one of the many possible examples of an issue that has nothing to do with building construction, but could be an important variable.

Air sampling is usually performed with the use of a small pump to draw a known volume of air through a collection device that catches mold spores. This sample is analyzed in the lab to determine what types of mold are airborne. It is important to also collect samples of outdoor air to serve as a comparison to the indoor samples. As mentioned previously, there are no standards for determining how much mold is too much, so comparisons to the outdoor and to the non-affected indoor environment are critical to assessing the effects of the building and the environment on the indoor air quality. As you can imagine, the interpretation of this data is inherently complex and problematic, so much so, in fact, that NYC officials say air sampling for fungi should not be part of a routine assessment, since air sampling methods for some fungi are prone to false negative results and cannot be used to rule out contamination. According to the American Industrial Hygiene Association, microbial problems in buildings have shown that perhaps 50 percent of microbial problems are not visible. Thus, destructive testing, such as tearing into the walls to see what is happening, can be warranted, if there is other evidence suggesting hidden problems.

It is my opinion that if enough mold is found to warrant negative air containment or relocation of the occupants, or when an occupant has complained of health susceptibility to mold, an independent Certified Industrial Hygienist or similarly qualified individual should be hired, that is, a professional who is not associated with the business of the contractor performing remediation, and who is paid by or on behalf of the building owner, but not by the contractor. This professional should perform inspections before work begins, write remediation specifications and observe the remediation at defined hold points, including clearance inspections after the work is complete. This serves as a check-and-balance mechanism that experience tells me is always worth the expense.

Many professionals who commonly investigate moisture problems in buildings, including myself, say that projects suffering distress often have many sources contributing to the situation. Be warned that, just because you found a problem, it doesn’t mean you found the problem. Since mold claims often end up in the hands of insurance agents and attorneys, documentation of all observations, conclusions, recommendations and work performed is crucial.

Remediation

For the builder or contractor, remediation means getting rid of mold. There is no definitive authority or standard, and the sources of information are the same as previously noted: NYC, EPA, CDC, AIHA and ACGIH. Some of the information sources refer to the U.S. Department of Labor’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration hazardous work standards, which mandate the level of protection and qualification of workers, and hazard-communication requirements. These OSHA standards traditionally relate to hazardous cleanup for chemicals or asbestos. Another source that is frequently referred to is California’s OSHA and its new sanitation-linked mold requirements (CCR, Title 8 3362).

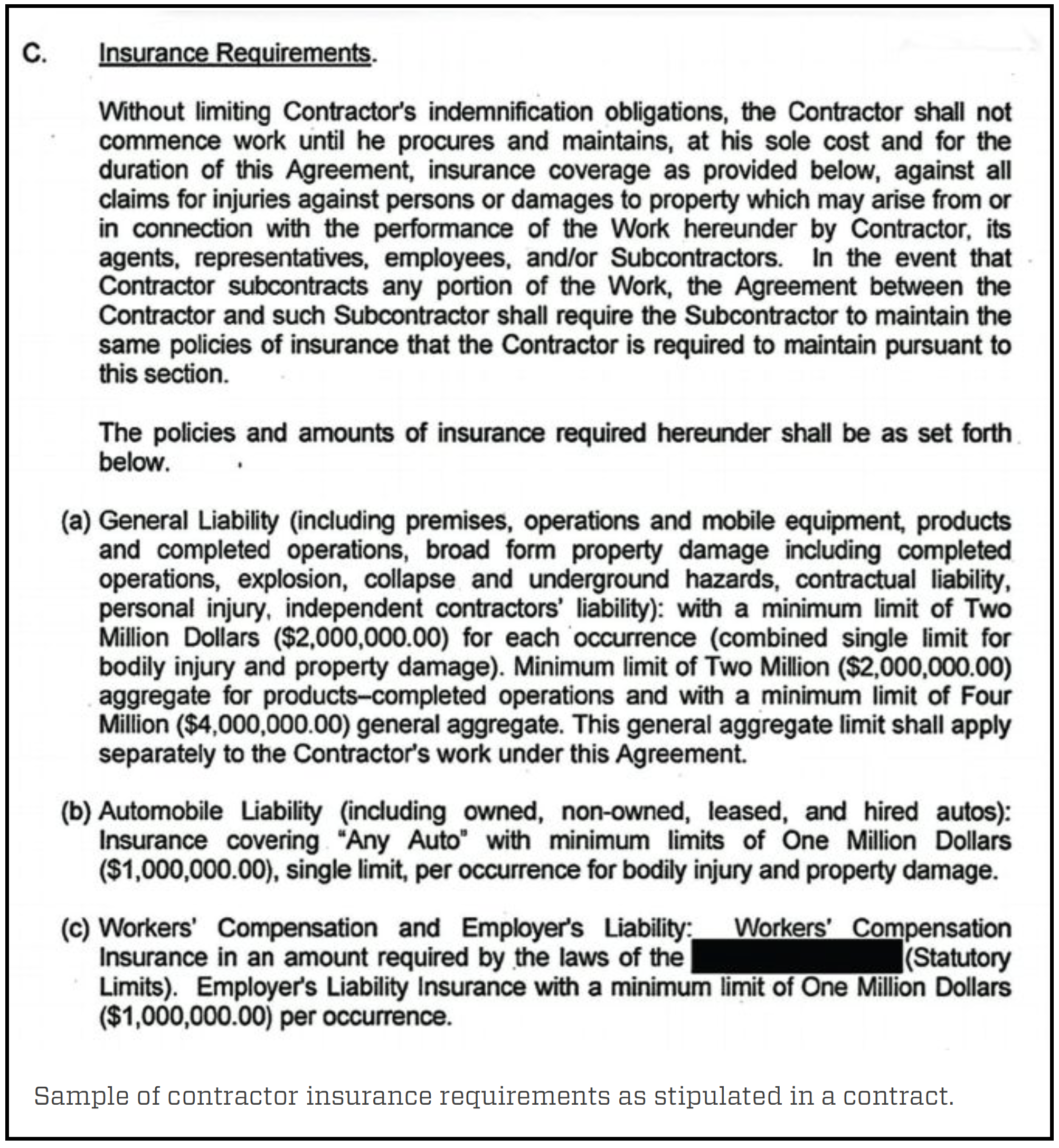

All authorities on mold stress the importance of repairing the source of the moisture before beginning remediation. A lack of attention to this critical activity may cause many current mold claims to return in the future. If the only professional hired is a CIH or other mold expert, he or she might not know enough about leak and moisture detection and repair to specify and oversee an effective, durable fix. For this reason, it is often necessary to have a building consultant on the team who can find the moisture source, specify a repair and make sure that repairs are performed correctly.

The professional who writes the remediation specification should indicate the level of containment required. Containment means keeping the moldy areas separated from those not affected, and is often accomplished by sealing doors, ducts and other means of escape for contaminated air, or by encapsulating the area with sheet plastic and sealing all of the seams. Most standards call for increasing levels of protection based on the surface area of mold that is found.

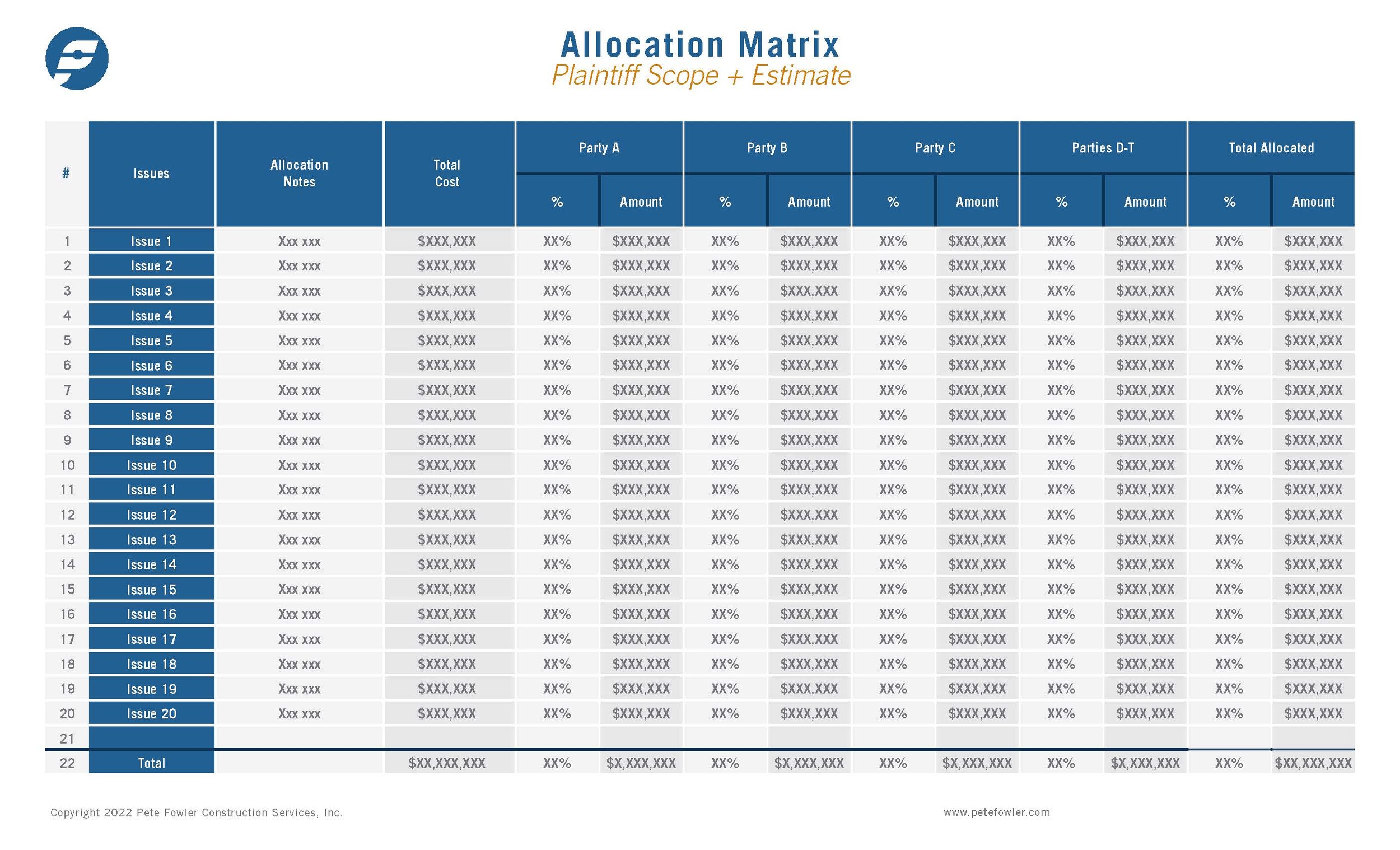

The table on p. 83 shows NYC requirements for containment and personal protective equipment. At Level I, no containment is required. Compare this to Level IV, where a complete isolation of the work area from occupied spaces, use of negative air equipment with high-efficiency particulate air filtration, inclusion of air locks and a decontamination chamber in the containment structure are required.

The referenced standards do not take into consideration the hidden mold often found in the course of remediation. When additional mold is found, it is important for the contractor or specifier to re-evaluate the level of protection required.

When containment is required, it is important to notify those who might be affected by the contamination, including building occupants and remediation workers. In the worst of situations, evacuation of buildings might be required. The NYC standards recommend that people who experience adverse health effects associated with exposure to fungal materials should be evacuated immediately from a building undergoing remediation, and they should remain out until the work has been completed. Other criteria for evacuation decisions include the size of the contaminated area, extent of health effects reported by building occupants and the amount of disruption likely to be caused by the remediation activities.

Remediation workers and anyone entering the remediation area may require personal protective equipment based on the corresponding level of contamination. At Level I, workers should wear rubber gloves and wear N- 95-rated masks (less than $5 each). At Level IV, this equipment could include a full-face respirator with twin HEPA-filter cartridges, mold-impervious head and foot coverings and a body suit made of a breathable material, with all gaps, such as those at wrists and ankles, sealed.

Treatment of damaged building components is different for various material types. Nonporous hard surfaces can be wiped clean. Soft materials that suffer contamination, such as wallpaper, wallboard, carpet and padding, are often removed and discarded. Wood framing requires evaluation based on the condition and extent of the mold or deterioration, and the ease or difficulty of replacement. Remediation can require removal of the mold with power tools such as grinders and sanders, then thorough cleaning with scouring pads and HEPA vacuum cleaners.

This is a very labor-intensive process, especially when the workers are wearing “moon suits.” If building contents are analyzed and found contaminated, they need to be meticulously cleaned or discarded. The value of the contents should be considered when making these recommendations, as it is sometimes found that cleaning will cost more than the items are worth.

Not long ago, contractors simply filled the old Hudson sprayer with a mild bleach solution and sprayed away if they found mold. In this use, the bleach solution is technically called a biocide. There are other biocides that were specifically formulated for the same purpose, but most authorities are no longer calling for their use, as repair of the moisture source and removal of the mold will suffice for remediation, and the odors and residual toxicity of biocides is thereby avoided. If there is mold floating around in the air, it stands to reason there might be some in the HVAC system. Guidance on remediation of contaminated HVAC systems is sparse. NYC recommends that the HVAC system be shut down during remediation activities. For Level Vb (see table on p. 83), air monitoring with the HVAC system in operation is recommended prior to re-occupancy. EPA and ACGIH refer to the EPA guide Should You Have the Air Ducts in Your Home Cleaned? The guide suggests having the air ducts in a home cleaned if there is substantial visible mold growth inside hard-surface ducts or on other components of the heating and cooling system. The service provider should agree to clean all components of the system and should be qualified to do so. Improper duct cleaning can cause indoor air problems or damaged ducts.

Clearance Criteria, the standards used for “final inspection” by the mold experts, as you might now expect, have no hard-and-fast rules. AIHA, ACGIH and EPA officials say that a remediation may be judged successful when two criteria are met:

➣ The problem that led to the mold contamination has been fixed

➣ Affected areas have been inspected and visible mold and molddamaged materials have been removed.

If air sampling is performed, the types and concentrations of molds measured indoors should be similar to those measured outdoors or in non-affected areas of the building.

ACGIH researchers add that concentrations of biological agents in any surface samples taken should be similar to those observed in well-maintained buildings or on construction and building finishing materials.

The training and qualifications of contractors and remediation workers is another hazy subject where the authorities refer to existing OSHA standards that deal with toxic cleanup work and hazard communication (again see Cal-OSHA CCR, Title 8, 3362). The OSHA references are mentioned only briefly, probably because there are no national standards specific to mold. These OSHA standards call for workers in heavy contamination areas to be trained to protect themselves and to be fitted with respiratory protection by a trained professional. Unfortunately, the type of “trained professional” is not specified.

Prevention

Given the dangers of mold, the necessity of preventing problems in the first place should be fairly evident. Build it right. But how, you ask? Training is the answer. Sources of information are abundant, but a single source that pulls the information together remains absent. I know of several groups that are trying to help, but they are probably a couple of years from seeing their visions complete, especially for residential construction (see Whole Building Design Guide, www.wbdg.org). For now, start your training program by contacting the National Association of Home Builders Research Center at www.nahbrc.org, reviewing its materials with your staff, making a list of the biggest risks you face, and starting to document and share your company’s best practices with your entire organization. Be sure to save this knowledge base in a structured way so that as new people join the organization, they too can share the accumulated wisdom.

Who needs training? Designers, builders—supervisors as well as workmen—suppliers, manufacturers and all building industry personnel. For window and door industry personnel, good training on proper installation methods and the prevention of problems can begin with ASTM International’s E 2112, the Standard Guide for the Installation of Doors, Windows and Skylights (www.astm.org). The American Architectural Manufacturers Association InstallationMasters training and certification program offers classroom instruction based on the ASTM standard (www.aamanet.org).

Also of interest is the upcoming ASTM standard, Design and Construction of Low-Rise Frame Building Wall Systems To Resist Damage Caused by Intrusion of Water Originating as Precipitation. The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, at www.ashrae.org, also has a wealth of information; you might start with the Handbook of Fundamentals sections on moisture in buildings.

Another aspect of building construction, often overlooked by residential builders, is testing. Assemblies that are not time-tested need to be thoughtfully designed, carefully installed and rigorously tested.

Consumer Education

Finally, education of consumers on what to expect from homes, and how to maintain them is crucial; in fact, it has now been legislated in California. A state Senate bill requires all builders to notify new homeowners of their maintenance obligations in writing. If the builder does not tell the owner that maintenance of an assembly is required, then that assembly had better last past the statute of limitations, or the builder could be on the hook. Owners also need to be taught to keep houses dry, identify leaks immediately and only allow qualified professionals to make repairs. Keeping relative humidity in a home or other building well below 65 percent is important. Builders need to make this easier with the design of the assemblies and training of the owners.