Managing Expert Costs

Managing Construction Quality

The Good Old Days

Successful construction projects used to go something like this: Owners would hire experienced, hardworking Architects and Engineers who developed plans and specifications that were not perfect, but good enough that experienced, hardworking General Contractors could hire experienced, hardworking Trade Contractors to do the work of making a project happen. We worked through the inherent difficulties of construction by working long hours, keeping our word and understanding that “stuff happens”. We accepted that no project was perfect, that people screw up, and knew that there was little use in crying over spilled milk. The satisfaction of a job well done carried us through the toughest days.

We didn’t spend much time telling specialists, like trade contractors, how to do their job. They had skilled tradesmen, the construction was relatively simple, and most contractors did things pretty much the same. If we had a contract, it was something the “suits” put together, and copies might not be sent to the jobsite since they had little or no connection to the “getting the job done”.

The New World

Construction professionals are living in a new world:

Consumers expect quality increases and price decreases in all products.

The building industry is not keeping pace with the quality and price advances many industries are

making.

Consumers are more litigious than ever and there is a proliferation of attorneys.

The building industry is not attracting the best and brightest young people.

The built-environment has been altered in the last 20years, including increased complexity, less

fault- tolerant materials, and tighter, slower drying buildings.

Consumers are more conscious of building-related health issues than ever.

In some areas, a lack of skilled construction labor makes the construction professional’s job even

more critical.

Construction Management

Our company delivers training in construction management and we have categorized the phases of project planning and management in a framework we call “The DBSKCV™ (pronounced “dib-skiv”) Method.”

Summary of the DBSKCV™ Method

Define the Scope of Work (this includes the design phase).

Budget: Identify how much the project will cost the contractors and owner.

Schedule when the construction will happen and share this information.

Contract (K): Who is doing what? Everyone should know what to expect.

Coordinate the construction.

Verify, document and communicate that everyone is doing what they should.

For details, please read The DBSKCV™ Construction Management Method.

Construction Risk Management

Growing legal risks, administrative issues, sky- rocketing workers’ compensation costs, increasing fees and taxation, and complicated insurance issues are only a few of the reasons why the price of construction is higher today than ever before. Managing construction risk is a full time vocation for many professionals and beyond the scope of this article (we do training on this too).

The ABC’S of Risk Management

A = Avoid Potentially Dangerous Situations (Impossible in construction)

B = Be Really Good At What You Do

C = Cover Your Assets

The ABC’s apply to Managing Construction Quality because (A.) we must face the fact that “risk avoidance” as a construction professional is impossible, (B.) being good at what you do means doing all you can to make sure a project succeeds, and doing a little bit of someone else’s job will sometimes become necessary, and (C.) the best “coverage” is avoiding problems by delivering work that meets expectations. Just accept buyers expect high quality and performance, even when they pay rock-bottom prices, and lawyers expect perfection; the former is hard, but easier than the latter.

Project Definition

The “Define” phase of construction management consists of documenting the work to be performed. This is usually graphic and written with plans, specs, references to codes and standards, and detailed “Scope of Work” documents. Getting a clear, specific and detailed project scope is the first step in the construction project management process and it is where a project’s “quality” should be established.

Some Quick Definitions

Plans and Details: Graphic representation of construction.

Specifications: Specs are the written representation of construction, which usually includes a

greater level of detail regarding construction performance, process, products, and quality.

Construction Contract: Agreement between two or more parties for the delivery of construction; plans and specifications are used as the definition of what is being bought and sold.

Standards: Documents, with graphic and written information, referenced by plans, specifications and construction contracts, which specify performance criteria and/or methods in greater detail than typical plans or specifications. Standards are created by standards setting bodies like ASTM, product manufactures, and industry trade groups.

Scope of Work: The written definition of what is being bought and sold. Usually articulated in writing by making a list or description of responsibilities and specific exclusions (work that is NOT included), with references to plans, specifications (prescriptive or performance based), and industry standards. I strongly prefer when the scope can be summarized in a 5-15 point list, or conform to the fundamentals of a 2 or 3 level “Work Breakdown Structure,” collectively representing 100% of the project scope.

Hold-Point: Critical time in the construction process where construction should stop for verification of conformance with plans, specifications, standards (including performance) and contracts. Verification can include inspection, testing, recording, and reporting.

In “the good old days” we left the details of “how to” to the trade contractors. After all, they are the specialists. But for the reasons stated above, leaving the details to trade contractors to work out among themselves has left a lot of projects in a less than enviable position: lack of integration, quality problems, re-work, leaks, lack of durability and on and on.

Owners or their representatives should no longer sign a one or two page “Proposal” from a contractor which serves as the “Scope of Work.” Such documents are not likely to contain information specific enough to ensure the scope is complete, to ensure that the parties are on the same page for quality or performance, and they lack adequate contractual protections.

Specification writers making obscure references to documents that are difficult to obtain is not new. But acquiring these documents is much easier due to the internet. It is now possible to “define” (design) our projects using readily accessible documents that we can use during the building process to make sure the on-site work is being installed and integrated correctly. This information needs to be integrated throughout the plans, specifications, standards and contracts. In practice, these documents should be created or referenced in the Define phase, referenced in the Contract phase, and used to compare the actual work in the field to the plan during Coordination and Verification.

Managing Construction Quality

There is no way to 100% guarantee project success and performance; the closest I have found is the use of a proven system.

Think of it this way: Construction plans and specifications are a hypothesis, and a hypothesis should always be verified. The hypothesis is that the designers and specialty consultants have composed a set of documents that are appropriate to build a project that will meet the performance expectations of the owners and applicable codes. The contractors on the project then work under the hypothesis that the design is functional, and that the work they do will also meet performance expectations.

Question: How do we verify our construction projects are going to perform?

Answer: (1.) During the define phase, we make sure our design hypothesis is reasonable by having someone with experience in building performance issues review, comment and recommend improvements; (2.) We make sure the plans, specifications, standards, and contracts are consistent in describing to the contractors who will install the specified material “what good performance looks like”; (3.) We establish a procedure to “verify” at specified Hold-Points during construction; (4.)During construction we inspect to verify conformance with the design (plans, specs, standards, and contracts). (5.) After the initial assemblies are installed, test them to verify performance, or build a mock-up and test it before construction (whichever is more cost effective).

Remember: We must be willing to administer consequences to project team members who don’t do what they promise. You will get resistance. If a contractor has signed a contract to perform consistent with a specified standard, it will sometimes take a strong will to make some of them perform.

ATTACHMENT: The attached Independent Quality Review spreadsheet is a matrix of optional activities one might perform or purchase from a consultant. The minimum activities required, for a third party to be of assistance in ensuring project quality, are identified; higher levels of service are like buying more insurance. Remember, this does not include doing the actual design. At a minimum, this is making sure the project definition is close to complete, and helping assure that proper installation and integration of the assemblies will lead to appropriate performance. Further work can ensure a connection between the plans, specifications, standards and contract scope of work documents.

Quality Management Plan

Here is the system, organized in the context of The DBSKCV Method. Remember, the DBSKCV Method is iterative, meaning we walk through all steps many times throughout the life of a project. We should go through the “D-B Loop” (e.g Define-Budget-Repeat) many times before moving forward.

Define

Architectural, Structural, and Specialty Design

Specification Writing

Referenced Standards

Quality Planning

Evaluation of plans and specs

Evaluation of referenced standards, and contract/ scope of work language review (Optional)

Hold Point Development and performance verification planning (Optional)

Mock-Up of assemblies and testing (Optional)

Recommendations (final) from Quality Review Consultant

Meetings or teleconferences between Quality Review Consultant and Owner, Designers and/or

Contractors (Optional).

Review of updated design, specification, referenced standards and contracts made in response to Recommendations from Independent Quality Review Consultant (Optional).

Budget

Update as necessary throughout the process. Make active decisions about “how much insurance to buy”.

Schedule

Establish Hold Points

Be prepared to stop the project if acceptable performance cannot be achieved

Contract

Connect the Plans, Specifications, and Standards, Quality Management Plan, including Hold Points, to the Contract and Scope of Work documents so that Quality does not “cost extra” (in change orders) during construction.

Coordinate

Make sure prime and trade contractors know the standards they will be held to during the Verify phase.

Coordinate actions at Hold Points in the construction schedule to verify quality of installations.

Verify

Visual Inspection at Hold Points to verify conformance with project definition (plans, specs, standards and contract scope of work documents) and to evaluate any on-site changes (Optional)

Testing to verify performance (Optional)

Final Report that might include: Quality control process, design summary, evaluation process, inspection summary, testing summary and on-going maintenance recommendations (Optional)

Project Name

Independent Quality Review

Communicating in Writing: A Training Article

Link to PDF download Communicating in Writing: A Training Article by Peter D. Fowler (2005)

Publication date: October 3rd, 2005

Author: Pete Fowler

Outline

I. Introduction

II. What’s the Point?

III. How To Write by Meyer & Meyer

IV. Prepare

V. Draft

VI. Work

VII. Practice

Communicating in Writing

Communicating in Writing is for anyone who needs to write letters, reports, proposals or email messages in a professional way. Excellent writing can be difficult, particularly if the subject is complex or contains technical information. This program offers a step-by-step method for preparing, composing and refining written communication.

Business people judge our professionalism, competence and even our intelligence by the written documents we deliver to them. If they are organized, clear, concise, and professionally composed then they are likely to take the information more seriously than if the document is disorganized, unclear, rambling and unattractive. Excellent communication establishes a standard of professionalism that business people take seriously.

No doubt there is work involved in any form of excellence: Our method for communicating in writing will help you to eliminate duplicative steps and have you working on activities that lead directly to excellent workmanship in document planning, construction, refinement and delivery.

Pete Fowler is active as a California General Contractor, Certified Professional Cost Estimator, Certified Inspector, Construction Consultant, author and speaker regarding construction topics. Focusing on construction projects and buildings suffering distress, Mr. Fowler has analyzed damage, performed testing, specified and overseen repairs, performed repairs as a contractor and testified on a variety of construction issues.

Outline (Expanded)

I. Introduction

Who Are We?

Why Are We Here?

Writing Is Work

II. What’s the Point?

Delivering Professional Solutions

Communication of Complex Information

Forest vs. Trees / Big Picture vs. Details

Analogy: Internet Home Page

Don’t Get Lost in the Details

Overcome Fears

Make Lots of Passes

III. How To Write by Meyer & Meyer

1.0 Preparation & Organization

1.1 Choose your format

1.2 Identify your points

1.3 Collect data regarding the points

2.0 First Draft

2.1 Compose your theme (Introduction)

2.2 Draft your outline (from the points identified in 1.2)

2.3 Write first draft

3.0 Polishing (make multiple passes to improve the previous draft): be accurate, be precise, be consistent, be brief, be fair, keep a steady depth, keep a steady tone, use an established layout (corporate look & feel), and use good grammar.

IV. Prepare

Choose Your Format

Write the first pass on “Why We Are Here”

Brainstorm Your Points

Research and Compile Information

V. Draft

Write the Introduction

Outline the Complete Work from Beginning to End (A to Z)

Re-Organize the Outlined Information

Write the First Draft

VI. Work

Write Or Refine The Executive Summary & Introduction

Identify Recommendations or Action Items, If Necessary

Read the First Draft Completely Through and Update (Create Draft #2)

Read Draft #2 and Update (Create Draft #3)

Have Someone Else Read Draft #3 and Ask Questions

Repeat the Reading and Updating As Necessary

Deliver: Media? Who Gets It? How Do You Confirm and Document Delivery?

VII. Practice

A. Prepare

B. Draft

C. Work

I. Introduction

Who Are We?

Pete Fowler Construction Services, Inc. (PFCS) is a professional construction services provider. We deliver professional solutions for building problems. Our services include expert construction consulting, inspection and testing, estimating, management, training, and testimony. Our team of construction professionals uses our unique, proven systems to deliver the most accurate and comprehensive solutions to best serve the interests of our clients, while maintaining our unwavering professional integrity. PFCS often serves as the interpreter of technical data related to buildings and the processes of construction. We create information that technical and non-technical professionals can understand and use to make informed, intelligent decisions.

PFCS is very special: There are few companies that can solve the problems we solve at a reasonable price. Continuously improving service delivery is being infused into the company DNA, and every important activity (i.e. business process) is being documented in our company organizational system.

Why Are We Here?

We are in the communication business. As already stated, “We create information that technical and non-technical professionals can understand and use to make informed, intelligent decisions.” This means taking a complex data set, organizing and analyzing it to create information, and finally summarizing the information in a way that non-technical people can understand and use.

We are here to learn to communicate in writing. Writing can be learned. If we are “knowledge workers” or professionals in any field, bad writing is “bad workmanship”. A professional who cannot communicate well in writing, is like a carpenter who cannot cut straight. On the other hand, you can make up for many shortcomings by consistently working through the process of writing until your written documents are excellent. If you deliver excellent written work consistently, you are more likely to be regarded highly in your field.

Writing Is Work

Naturally, if you are writing a one-page document, the steps to completion will go quickly. But remember, they are always the same steps.

If you like working toward the creation of excellence and elegance, then you will like the writing process (eventually). If you don’t, then you won’t. Writing well in business is not a matter of artistry; it is a matter of skill. Skills are won through practice. I don’t know of any other way to develop a skill. The first time you compose an excellent piece of writing it will take you 5 to 10 times longer than “normal”. The second time it will take you 2 to 5 times longer. The third time it will take twice as long. Some time between the fourth and 50th time you compose an excellent piece of writing it will take you the “normal” amount of time. This is how life works. If you don’t like the idea that practice makes perfect, take a number. We are all frustrated by it, but once you are past the learning phase, your capacity as a professional will have been elevated into another league.

II. What’s the Point?

Delivering Professional Solutions

Solutions: A “solution” is a process that can move a situation from an undesirable state to the best available alternative. Merriam-Webster defines solution as: 1: an action or process of solving a problem; 2: an answer to a problem; 3: a set of values of the variables that satisfies an equation; 4: a disentanglement of any intricate problem. We need to decide the scope of the solution we will be addressing in each of our pieces of written work.

Professional: Professionalism is the effective, proficient and courteous handling of the activities involved in your work. Merriam-Webster defines professionalism as: “Exhibiting a courteous, conscientious, and generally businesslike manner in the workplace.” We need to decide what about our written work will be required to consider it “professional”. In their book How To Write, Meyer and Meyer suggest: be accurate, be precise, be consistent, be brief, be fair, keep a steady depth, keep a steady tone, use an established layout (PFCS corporate look & feel), and use good grammar. I agree with the Meyer’s sentiments completely.

Delivering: We need to think of the term “deliver” in 2 distinct ways: (1.) physical “Deliverables” such as documents, e-mail messages, spreadsheets, plans, Power Point Presentations, etc… and (2.) the style of our “Delivery”. In this training session we are dealing with both the creation of a “Deliverable” document, and the style of “delivery” that will give the recipient cause to hold you and your work in high esteem. We need to decide what our delivery of these deliverables is going to say about us, about our competence, our work ethic and our dedication to excellence.

Communication of Complex Information

Remember that any complex or voluminous set of information (including the American Civil War) can be presented in various forms and lengths:

The Civil War can be described (summarized) in 1 paragraph. For example (113 words):

The U.S. was founded in 1776 and was divided socially and economically in the years prior to Abraham Lincoln’s 1860 presidential victory, particularly by the issue of slavery that was practiced in the agricultural Southern states but not in the industrialized Northern states. Early in 1861 the South separated from the Union, set up a government, Lincoln was inaugurated as President, and hostilities broke out, as the North was determined to hold the Union together at any cost. By the end of 1865 the South had surrendered and slavery was abolished by the 13th amendment to the US Constitution. The combined death toll was grater than 500,000 and over 400,000 troops were wounded.

The Civil War can be described in an article.

The Civil War can be depicted in a 2-hour movie (there are many).

The Civil War can be depicted in a multi-episode documentary (on PBS and others)

The Civil War can be depicted in a book (there are many).

The Civil War can be depicted in a series of books (there are many).

The Civil War can be studied as a life-long pursuit (there are many scholars).

When communicating complicated subject matter, remember: If you can’t summarize your point in a paragraph or two, then you have not worked hard enough on it. When a subject large enough to fill a lifetime of study can be summarized into one paragraph, any thing can. I don’t mean to suggest that a tremendous amount of detail can be transmitted in a paragraph; but the mind of a layperson needs constant orientation. By summarizing your material for orientation, then diving into the supporting details as necessary, you will more effectively communicate.

Forest vs. Trees / Big Picture vs. Details

The trees are only important in the discussion when we understand what forest we are in. Don’t talk about trees until you have told the reader what forest you are in. This is a big problem that causes a lot of problems.

Both the big picture and the details are important. We each need to recognize which we grasp and communicate better. Some people are naturally oriented to big picture concepts and some dig into details. Whichever you are, a big picture or details person, you will need to address the one you are weak at. If you do, your written communications are much more likely to be universally accepted as excellent work. Don’t forget this, and don’t forget where your strengths are so you can address your weakness.

Analogy: Internet Home Page

Think of an elegantly designed internet home page. It is easy to understand the scope of the entire site from a good home page. You can understand the navigational scheme when they are well designed. Information is organized logically and when you click around you find what you would expect to find. A good document covering a complex subject will operate much the same way. You need to be concise enough to get your point across, but also support your conclusions with evidence and references to further information, if necessary.

Don’t Get Lost in the Details

Getting lost in the details is a horrible sin. It wastes your time, and worse, it wastes the time of the reader.

Overcome Fears

Many of us are afraid to do things badly. I admit it; I don’t like it when I am not good at some thing. Excellent writing ability, as we have said, is a skill that comes with practice. Good writers do a lot of writing.

Using this step-by-step process will help. Do not try to short-cut the process by writing in one pass. Writing that will make you stand out as a top-notch professional will take time and energy, but you will succeed. Let your steps be small ones and celebrate when you get to each of the milestones. If you are working on a computer, consider printing drafts at key milestones and savoring the victory of completing these steps.

Make Lots of Passes

As you will see in the step-by-step list of activities below, excellent writing requires work. This work must be made in passes. Run through the entirety of the work from A through Z many times. This is in contrast to the philosophy of spending the time in trying to make some thing perfect on the first pass. It is my hard-won experience that trying to make it right on the first pass gets you “lost in the forest”, because you are concentrating on “trees” rather than the big picture. Passing across the work from A to Z as rapidly as possible ensures that you always have perspective on the entire body of the work.

III. How To Write by Meyer & Meyer

1.0 Preparation & Organization

1.1 Choose your format

1.2 Identify your points

1.3 Collect data regarding the points

2.0 First Draft

2.1 Compose your theme (Introduction)

2.2 Draft your outline (from the points identified in 1.2)

2.3 Write first draft

3.0 Polishing (make multiple passes to improve the previous draft)

3.1 Be accurate

3.2 Be precise

3.3 Be consistent

3.4 Be brief

3.5 Be Fair

3.6 Keep a steady depth

3.7 Keep a steady tone

3.8 Use an established layout (corporate look & feel)

3.9 Use good grammar

This is a great book. It is available from Amazon for less than $10.00.

Summary: Writing is critical. Writing is a process. The writing process is always the same 3 steps (organize, draft, polish). Don’t try to do step 2 until you have completed step 1. Some of the steps in writing involve not writing. Figuring out the theme (in a few short sentences) is a critical step and might require some time. Writing takes tenacity. We are entitled to our own opinions but not our own facts. Be clear and concise and cut unnecessary stuff. Use an established layout. Read the work out loud to check for grammar. If there is time, always review the work one more time. Communicating your intended meaning to the reader is the most important thing.

IV. Prepare

Choose Your Format

Most business related writing should rely on a standard format. Our company has a “corporate look & feel” for all document types, including reports, proposals, letters, faxes, and e-mail messages, to which we adhere. All written documents can all be formatted according to some standard; I recommend you establish a standard and stick with it.

Make sure you use headings, sub-headings, numbered lists, bullet-point lists, bold letters and other identifiers to aid the reader in breaking up a longer work into bite size chunks.

For PFCS, there is no reason to reinvent a format. For each of our services we have a standard set of example “deliverables” to choose from as a format. These Include:

CC: Report, Summary of Issues, Opinion Letter

PA: Residential Property Assessment, Commercial Property Assessment, Testing Summary and Analysis

CE: Preliminary Estimate (Plaintiff by Residence), Preliminary Estimate (Defense by Issue), New Construction (by CSI), Budget, Budget / Payment Application

CM: Proposal for CM Services, Letters, Prime Contracts, Subcontracts, RFI, Meeting Notes

TE: Presentation Materials

EW: Opinion Letter

Write the first pass on “Why We Are Here”

This is like the “Vision Statement” in project planning. It might be one sentence or it might take a paragraph. Remember, if you would like the audience to take some action, be sure it is clear what your recommendations are.

For example:

This report will (1.) give a basic description of the property, (2.) list the problems identified by the owner and those we found during our 1-day of inspection, and (3.) outline the steps we feel need to be taken to resolve the problems.

This correspondence is to explain our position related to the denial of the request for payment by the roofing contractor, due to components having been defectively installed, and the steps required for the roofer to receive complete final payment.

This memo is a response to a letter from the owner alleging project delays, identifying additional expenses, and assigning 100% of the blame to the contractor. The correspondence will include two step-by-step scenarios for project close-out.

This e-mail message serves as a request for proposal (RFP) to a drywall contractor for a new single-family home construction and will identify the location, basic scope of work, exclusions, insurance requirements, and payment information. In addition, I will include our contact information and information for how plans can be procured.

Once this activity is complete, you can judge the content of your writing to ensure it is supporting the purpose of the work.

Brainstorm Your Points

What are the key points you want to make? This is not the time to make detailed supporting documentation of each point, so don’t let yourself get too detail oriented here.

For example, the points for the first bullet point in the list above might be:

Property Description: Single Family Residence in San Juan Capistrano

Problems: Leaking Doors (2 sets), Leaking Roof (3 locations), Damaged Flooring (2 locations), electrical problems (3 locations), water in fireplace during storm, etc…

Steps to Resolution: Testing, report, Scope of Work, budget, RFP, contract, perform repairs, test repairs.

Research and Compile Information

This is where you hit the phones, the internet, the books, your colleagues, or any other source of information necessary to get your thoughts together.

Examples of research in our current sample situation might be to compile some articles on weather-stripping and painting for the deteriorated French doors, and flush-mounted vinyl sliding glass doors for the leakage at the sliding doors upstairs.

V. Draft

Write the Introduction

This is where you finally get to do some writing. Review the following example:

The property involved is a single-family semi-custom residence constructed in approximately 1980 and located at the above noted address in San Juan Capistrano, CA. The home is now owner-occupied. The current owners purchased the residence in November 1998, did not have a residential home inspection performed, do not know the circumstances of original construction, nor do they possess construction drawings from the time of construction. AsBuilt drawings are available in various formats (including PDF).

PFCS has had one on-site meeting with the owner and performed a visual inspection 1/10/05. We were contacted due to leakage and site ponding, caused by the recent rains, to perform a visual only inspection, interview the owners, compose a summary of our observations and deliver recommendations to repair problems with the property.

This is where you want to include the “who, what, where, when, and why” of the current situation. Any basic information that is left out here can cause the reader confusion.

Here is another example:

We are requesting proposals for performance of all drywall (gypsum wallboard) work on a new single-family semi-custom home in San Clemente, CA. The proposal needs to include all drywall work for a complete job, with a smooth coat finish achieving the highest standards (GA-214-96 Level 5) for quality as specified by the Gypsum Association (www.gypsum.org/download.html). Payments will be distributed every other week on standard payment application forms. $500,000 Commercial General Liability (CGL) insurance policy and references required to bid. Plans can be viewed at 927 Calle Negocio, Suite G, San Clemente, CA 92673. Telephone 949-240-9971.

Before writing any further, now figure out the complete contents of your document. Keep in mind the introduction that you just wrote, as well as the “Why Are We Here” section.

For example:

Executive Summary

Introduction / Why Are We Here?

Called by owner

Investigate water intrusion and ponding

Offer recommendations

Property Description

Single Family Residence

In San Juan Capistrano

Constructed approximately 1980

Approximately 3,200 square feet

Slab on grade construction

Wood frame, siding & stucco,

Aluminum windows except 2 vinyl replacement windows at 2nd floor master bedroom

Wood shake steep slope on front and cap sheet low slope roof at back

Problems

Leaking Doors (1 set and one slider)

Deteriorated Doors (2 sets)

Leaking Roof (3 locations)

Damaged Flooring (2 locations)

Electrical problems (3 locations)

Water in fireplace during storm

Drainage problems (4 locations)

Clogged sub-grade drain system

Steps to Resolution

Testing

Report

Scope of Work

Budget

RFPs

Contract

Perform repairs

Test repairs

Re-Organize the Outlined Information

This is a key activity. Beyond this point, structural changes get complicated. You might want to print the document and take a red pen to it. You might want to review it with some one to make sure the information flows as you would like it; you may be surprised at what comes out of your mouth when trying to tell the story from the first pass of your outline.

Write the First Draft

This is where the work begins; and it should go fast, considering all of the work you have done to prepare.

This is where people who don’t write so well begin. Don’t follow their bad example.

When you are done, you might consider printing and reviewing the document with a red pen in hand.

If the document is large and complex, you will probably want to make this first draft what I call the “Stream of Consciousness” pass. In this draft do not try to put any REALLY detailed information. Don’t stop typing until all of the information that is in your mind has been typed onto the pages of the report. The next pass can be the one where the calculations and detailed information is updated.

VI. Work

Write or Refine the Executive Summary & Introduction

What are the important points of your work? And don’t say “all of them”. Remember back to the American Civil War discussion; some people want or need a brief synopsis – so give it to them. If the document is only a couple of pages long, then this can be omitted, but if it gets beyond 4 pages, then you definitely need an Executive Summary, or some section which serves the same purpose at or near the top of the document.

Identify Recommendations or Action Items, If Necessary

If you want action, you have to ask. If some of the actions in the recommendations section are required by you or your organization, make sure that you do them.

Read the First Draft Completely Through and Update (Create Draft #2)

I usually print mine and go through them with a red pen. It is usually a blood bath. This is the activity that separates lucid and effective writers from the rest of the pack.

Read Draft #2 and Update (Create Draft #3)

Again, I usually print mine and go through them with a red pen. This time, there is more satisfaction because I am just polishing. The document starts to look very professional.

Have Someone Else Read Draft #3 and Ask Questions

This is a luxury, of course. But, if this document is important, it is worth the work.

Repeat the Reading and Updating As Necessary

This is going the extra mile. When it counts, do it.

Deliver: Media? Who Gets It? How Do You Confirm and Document Delivery?

How are you going to send this? I hate to see beautiful documents or reports that contain photographs sent via facsimile. They look worse for the wear, when we now usually have the option of printing them to an electronic format like PDF (portable document format) and sending them electronically via e-mail.

In our office it is critical that all written communication that comes in or leaves the office is documented in the project file. We need to know who created it, when it went out, who it went to, and sometimes we need to confirm receipt. There are lots of ways to do this, but making sure it gets done can be crucial.

VII. Practice

A. Prepare

Choose Your Format

Write the first pass on “Why We Are Here”

Brainstorm Your Points

Research and Compile Information

B. Draft

Write the Introduction

Outline the Complete Work from Beginning to End (A to Z)

Re-Organize the Outlined Information

Write the First Draft

C. Work

Write Or Refine The Executive Summary & Introduction

Identify Recommendations or Action Items, If Necessary

Read the First Draft Completely Through and Update (Create Draft #2)

Read Draft #2 and Update (Create Draft #3)

Have Someone Else Read Draft #3 and Ask Questions

Repeat the Reading and Updating As Necessary

Deliver: Media? Who Gets It? How Do You Confirm and Document Delivery?

Back-Up / References / Sources of Information

VII. Practice - Blank page 1: Prepare

VII. Practice - Blank page 2: Draft

VII. Practice - Blank page 3: Outline

VII. Practice - Blank page 4: First Draft

VII. Practice - Blank page 5: Refine

How To Write by Meyer & Meyer www.amazon.com

We Shall Not Fail: Chapter 3 by Sandys & Littman

Introduction to Business Communications – 1 Hour Video DVD in physical library

PFCS Presentation Development Method Library under Training & Education

5C 04-12-21 Cost Review.pdf PFCS Project File (Wakeham 04-157)

5E Executive Summary 03-03-28.pdf PFCS Project File (Geller 01-164)

5C Report of Testing Results 04-06-10.pdf 00-000 Sample Property Project PA

11 1A 03-12-09 L to ATY RE Investigation.pdf 00-000 Sample Consulting Project CC

11 1A 03-10-14 L to ATY re Observations.doc 00-000 Sample Consulting Project CC

03 1A 03-09-10 L to ATY RE Investigation Proposal.doc 00-000 Sample Consulting Project CC

DBSKCV Construction Management Method

Link to PDF download The DBSKCV™ Construction Management Method by Peter D. Fowler

Publication date: January 1st, 2005

Author: Pete Fowler

What is this DBSKCV TM “Method”

Since the time of the ancient Greeks, humans have been creating and using problem solving "methods" to help us structure situations to aid in identifying the best available alternatives. Some examples of these methods include:

• Classic Problem Solving (Where are we? Where are we going? How do we get there?)

• Scientific Method (Observe, Hypothesize, Predict, Test, Repeat)

• Alcoholics Anonymous' 12-Steps (admit, believe, decide, inventory, confess, prepare, ask, list, amends, continue inventory, pray for knowledge, help)

• Dr. Deming's 14-Points for Quality Management (purpose, philosophy, variation, suppliers, improvement, training, leadership, fear, barriers, slogans, eliminate MBO, workmanship, self-improvement, transformation)

• Six Sigma for Process Improvement (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control)

• Franklin Covey's Project Management Method (Visualize, Plan, Implement, Close)

• Project Management Institute's 9 Project Management Categories (Management of Scope, Time, Cost, Human Resource, Risk, Quality, Procurement, Communication, Integration)

• ASTM Standards: E 2018 Property Condition Assessments, E 2128 Standard Guide for Evaluating Water Leakage of Building Walls, E 1739 Guide for Risk Based Corrective Action.

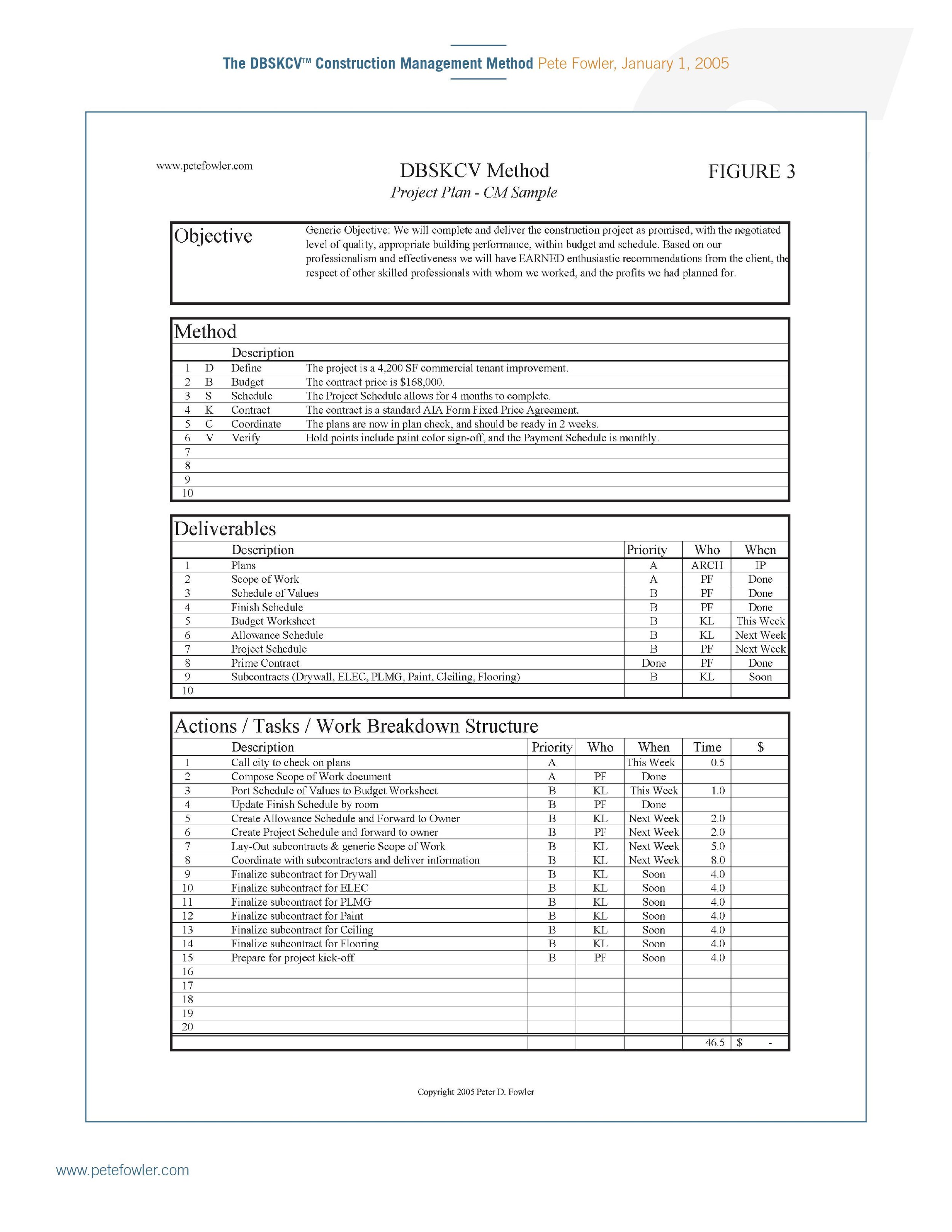

The DBSKCVTM (pronounced "dib-skiv" - DiB-SKCiV) Method is a six-category framework to aid construction professionals in achieving construction project objectives. The DBSKCVTM Method begins with a Project Plan (Figure 1), which starts with identification of the project Objective. We then use the DBSKCVTM Menu of Deliverables (Figure 2) as a menu to select documents or actions that will aid us in moving from where we are to our stated objective. The final step in project planning is to create a step-by-step list of actions. First we plan the work, and then we work the plan. Take a minute or two to review the plan and menu.

This is harder than it sounds. Construction people have a bias toward action; which is a good thing -- we like to see things happen. But we need to resist the temptation to do work before planning. This way, we can be sure to not waste time on unnecessary activity, which is a common source of project failure.

What is Construction Management (CM)?

The Construction Management Association of America (CMAA) says the 120 most common responsibilities of a Construction Manager fall into the following 7 categories: 1. Project Management Planning, 2. Cost Management, 3. Time Management, 4. Quality Management, 5. Contract Administration, 6. Safety Management and 7. CM Professional Practice. This includes specific activities like defining the responsibilities and management structure of the project management team, organizing and leading by implementing project controls, defining roles and responsibilities and developing communication protocols, and identifying elements of project design and construction likely to give rise to disputes and claims.

Why is Construction and Construction Management Important?

Construction professionals are living in a new world. The following social & economic realities make construction, CM and professionalism in construction critical:

• Building construction is a fundamental component of human society.

• Construction constitutes nearly 10% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

• Consumers are expecting quality increases and price decreases in all products.

• The building industry, in general, is not keeping pace with the quality and price improvements that many industries are making.

• The building industry is not attracting the brightest young people into the industry.

• Consumers are more litigious than ever and are becoming more and more so.

• There is a proliferation of attorneys.

• The built-environment has been altered dramatically in the last 20 years.

• Consumers are more conscious of building related health issues than ever.

• In some areas, a lack of skilled construction labor makes the construction professional's job even more critical.

Project Planning and Management

There is no way to 100% guarantee project success. The closest I have found to a guarantee (and I have been looking long and hard) is to hire highly experienced geniuses, or to use a proven system. So if you are not a genius, or can not afford an entire team of them, you better read on.

It is also my experience that planning always saves time. As I mentioned before, construction people want to see things happen and it takes discipline to resist the temptation to start working before completing the Project Plan. Remember: Planning is the closest we can get to a guarantee of project success.

Growing legal risks, administrative issues, sky-rocketing workers' compensation costs, increasing fees and taxation, and complicated insurance issues are only a few of the reasons why the price of construction is higher today than ever before. In addition, managing risk and facilitating a smooth operation are reasons enough to use a system for the management of your project.

We have all heard the adage: "Good people are hard to find." I think good companies are even harder to find. All great businesses create systems that help good people achieve the goals of the company. Most companies, particularly in the construction industry, rely on individuals to develop their own systems. This means the individual has to be some kind of genius. Geniuses are hard to find, but not as hard to find as good companies with good systems.

The construction industry is attracting fewer "geniuses" than other industries. We need to make it easier for construction managers to succeed, giving them tools and techniques to keep promises, balancing the big three (cost, quality, and time), to offer continuously improving value (more quality for less cost and time), and to earn the money they could make in competing industries. Teaching construction managers to plan profitable projects and manage them through fruition is a fundamental that the construction industry is not doing well enough.

Dealing with contractors and subcontractors requires skill, professionalism, and a system. The quality of contractors ranges from excellent to criminally incompetent, which can make the process range from complex but satisfying, to nightmarish and costly. We can not rely on contractors to act professionally – if they do, let it be a pleasant surprise, and when some don't, we must have a system in place to manage the problem. My experience suggests that a nice but incompetent contractor might cost us more than a competent criminal. Don't let yourself be the victim of a contractor's lack of sophistication. If you use a process to guide you in dealing with problem contractors and project pitfalls, success is much more likely. The right planning activities at the beginning of the project will equip you to deal with the incompetent or the unscrupulous.

Summary of the DBSKCV™ Method

• Building construction is a fundamental component of human society.

• Construction constitutes nearly 10% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

• Consumers are expecting quality increases and price decreases in all products.

• The building industry, in general, is not keeping pace with the quality and price improvements that many industries are making.

• The building industry is not attracting the brightest young people into the industry.

• Consumers are more litigious than ever and are

Each of these categories could be books by themselves. The idea here is to fly over the subject of Construction Management so that we see the big-picture. We need to understand the forest, so we don’t get lost in the trees. Dealing with details before understanding the big picture can be dangerous. In construction, dangerous means expensive.

I. Define the Scope of Work

The “Define” phase of construction management consists of documenting the work to be performed. This is usually done graphically and in writing with plans, specifications, references to codes and standards, and detailed “Scope of Work” documents. Getting a clear, specific and detailed project scope is the first step in the construction project management process.

See the DBSKCV™ Method Menu of Deliverables (Figure 2) for the most common scope of work documentation. Depending on the type of project, this is sometimes the work of architects and engineers, but many projects are defined by owners and contractors.

Complete, detailed scope of work documentation allows parties a mutual understanding of what is being bought and sold. My company has consulted on many projects where the owner and the contractor were in dispute and the root cause was a lack of clarity from the beginning. A good “scope of work” is like building on a proper foundation and should identify the quantities and locations (“scope”) of the work as well as materials, specifications, methods and standards of workmanship. Until you have specified in writing the location, size, shape, materials and workmanship you are envisioning for your project, you are not ready to move forward in the planning process. The “scope of work” (i.e. mutual understanding of what is being bought and sold) should be updated as necessary throughout the project.

Keep in mind that the specifications or methods that are defined in the Scope of Work can mean the difference between long term success and failure. As an example, the right paint specifications can double the life of a paint job. If the owner thinks they are buying a 10-year paint job, but the specification will not deliver, a “re-meeting of the minds” might be called for.

Owners or their representatives should not sign a one or two page “Proposal” from a contractor. The “Scope of Work” in such a document is not likely to contain information specific enough to protect the owner if the workmanship is poor. In addition, the contract language will not protect the parties as well as a more complete and professional contract.

II. Budget

Estimating and budgeting are stand-alone areas of professional practice which some construction professionals dedicate their entire careers to. A good estimate for construction is based on lots of assumptions, including the scope of work. If the scope is a moving target, so will the construction costs. Direct costs of construction are usually categorized by Labor, Materials, Equipment and Subcontractors. Most good contractors estimate what they think direct construction costs will be, and then add for overhead, profit, other project costs and contingency, to come up with a contract price.

Total construction cost is made up of so many little pieces that it can become incomprehensible without a system for management. My company has worked on projects in dispute where the records were maintained so poorly that it was impossible to determine the exact costs of construction.

The importance of managing the budget cannot be understated. Before, during and after construction, the construction manager should always know where the project stands relative to the budget. During the course of construction you should know exactly what has been paid and the approximate amount remaining to complete the project.

Keeping an Expense Register that is coded to allocate all expenses is a critical activity so the original and updated Schedule of Values can be compared to the actual project expense. A Budget Worksheet (similar to AIA form G703) should be setup at the beginning of the project and maintained through project close.

III. Schedule

A schedule can take many forms, including Barr / Gantt charts, or CPM (Critical Path Method) Schedules, but the simplest is a list of activities and when they will be performed. A competent contractor should be willing to put a schedule in writing. The owner should add some contingency time of her own. The schedule gives everyone an idea of what will go on and when and will serve as a measuring stick to compare plan to actual progress. With this tool, everyone can identify problems early.

Scheduling is about communication. Successful project management requires communication of expectations with everyone involved: owner(s), designers, contractor(s), government agencies, subcontractors, suppliers, and more. Each activity in construction is usually pretty simple; the greatest difficulty is often in coordination of so many parties. There are often more things to do and coordinate than people can keep organized in their heads. Unfortunately, many projects never have a schedule put to paper, or even if they have one at the beginning, it is not used as a management tool throughout construction.

IV. Contract

A contract is a binding agreement. It should be used as a communication tool to make sure that all parties understand and agree exactly what is being bought and sold. Like any other powerful tool, it can be dangerous, so be careful. Don’t let the excitement of a big project, a smooth talker, or a busy schedule allow you to gloss over the details

A prime construction contract is an agreement between the owner and a contractor. A subcontract is an agreement between a prime contractor and some other contractor who will perform all or a portion of the work covered in the prime contract. Thus, if an owner contracts directly with a “subcontractor” like a painter, this is not a subcontract; it is a prime contract. Prime and subcontractors have different rights and responsibilities. Unfortunately, some prime and sub-contractors do not operate professionally.

All contracts for construction should be in writing. We will hit only the high-points here, but at a minimum, a construction contract should contain:

• Full contact information for all parties to the agreement, including contractor license information, physical location of all parties, and a description of the property in question.

• Detailed “Scope of Work” with material, equipment and workmanship specifications. This might include plans, and written specifications describing the work in detail, a list of fixtures, etc...

• Contract Price (Schedule of Values, Allowance Schedule, etc…)

• Payment Schedule

• Construction Schedule and any consequences for failure.

Change Orders are a natural part of construction and a contingency for them should be built into the budget. Change orders become a part of the construction contract, should always be in writing, and should be negotiated and signed at the time the change occurs, not at the end of the project.

A Payment Schedule should be negotiated at the time the contract is signed. Try to never pay more than the value of the work in place. That is, if the project is 50% complete and you have paid 75% of the contract price, then you are in a dangerous position.

Contractors’ lien rights are a complicated collection of legal protections to make sure contractors get paid for improving property. Collection of lien releases verifies that contractors have been paid and protects the property from liens.

V. Coordinate

The “coordinate” phase of construction management takes our planning and puts it to work. We spend a lot of time and energy in the define, budget, schedule, and contract phases, even though we get none of the satisfaction of seeing physical work take place. Remember: When the time to perform has arrived, the time to prepare has passed. If you effectively defined, budgeted, scheduled, and contracted the project, then this phase will go as smoothly as construction ever goes (so there will still be some problems to solve). Coordination of contractors, subcontractors, materials, equipment, inspections, changes, unforeseen conditions, personalities and forces of nature are always a challenge.

In addition to the real “work” of a construction project, the coordination phase is where the miscommunication, screaming matches, fistfights, litigation and endless frustration often occur; we could also call this phase “Herding Cats”. Managing a project from beginning to end requires a combination of construction knowledge, management skills, political savvy, and patience. While construction is usually a simple assemblage of labor, material, equipment and subcontractors, there are so many moving parts that things regularly can and do go wrong.

Management of construction requires effective communication. Let’s make this as clear as possible: OVER COMMUNICATE, in writing. If you have never read The One Minute Manager, do so before you start your next project; it takes less than 2-hours and will save more than that in the first week. The point is: (1.) Figure out what good performance looks like, communicate and document it in writing, and get agreement that everyone shares your vision (One Minute Goals). (2.) Make sure there are rewards for good performance because we all want to feel good about doing good work (One Minute Praisings), and (3.) have the courage to administer consequences for poor performance (One Minute Reprimands).

You need to have a filing system for your project and religiously document and file the mountain of project information. There are things that should be performed regularly to keep the project progressing. Forms that might be used and/or updated include: Scope of Work, Specifications, Finish Schedule(s), Schedule of Values, Budget, Expense Register, Project Schedule, Change Orders, Purchase Orders, Contacts List, Daily Log (who did what, how long it took, noteworthy conversations, etc…), Correspondence, Safety Meeting Minutes, Accident Reports, Inspection Check-Lists, Municipal inspection information, etc.

VI. Verify

Verifying that the construction is proceeding as planned is critical. This is where we compare our progress to plan. Big problems start small. When we find variations from our plan, we use our documentation system to memorialize them. Remember that property improvement contractors have become the #1 consumer complaint in the U.S.; if you do not want to be a sad statistic, then problems need to be nipped-in-the-bud.

The building department might want to inspect at specified points for life-safety issues. If someone says no permit is required, ask them to put it in writing, or call the municipality. Remember: The building department is not where inspection ends. We have listened to scores of owners bemoaning their fate saying, “Where were the city inspectors?”, when they had buildings that leaked or were otherwise constructed poorly. The owner or representative will want to “verify” at various hold-points to ensure the quantity and quality of workmanship. There may be special assemblies like roofs, decks, windows or weather-resistive assemblies that should be tested to make sure they were constructed appropriately

The contractor will be asking for payments based on the Payment Schedule and you will need to verify the work is complete and built to the standards established in the “define” phase of planning. In addition, the owner will want to collect lien releases for work that is completed and paid.

Conclusion

Remember: 1. Use a system to document your objectives and the process of construction, in writing. 2. Communicate with all of the players in the process. 3. Put everything in writing: People are more committed and more accountable when they have put all their promises in writing.

Dangers of Mold Lie in Ambiguity

Dangers of Mold - by Pete Fowler. Published by Window and Door Magazine in 2003

Lack of accepted standards and a large number of variables mean costs can escalate quickly

You’ve probably seen it on TV, and read about it in newspapers and magazines. You can find more information about it on the Internet than you could ever read, even if you quit your job to do it. For window and door manufacturers, distributors, dealers and installers, or for a business that is related in any way to building construction, real estate or insurance, mold is a scary subject.

In 1999, mold claims only came along with a small percentage of the projects I worked on as a construction consultant involved with insurance claims and litigation issues. Now claims without allegations of mold are equally rare, in Southern California at least. Have the natural or built environments changed, causing a spike in the amount of mold growing in California, or is the interest in mold due to changes in the insurance and legal environments?

The health issues that have been widely reported in the media are a real concern, but the problems do not stop there. The “dangers of mold” also include: expenses for expert inspection and testing; remediation; alternative living expenses; legal costs; business interruption; insurance coverage with skyrocketing costs or a lack of availability; bad publicity; the ambiguity in all of the above due to a lack of standards; and more.

There is an enormous volume of confusing and contradictory information available on the topic of mold and a rapidly growing population of folks claiming to be “mold experts.” We’ve all heard the horror stories, but what do you need to know as a window or door manufacturer, distributor, dealer or installer suddenly drawn into a mold-related problem? This article is designed to help you cut through the haze, give you an idea of who you should have on your team, and tell you where to find reliable information. With a little background, you’ll be able to tell if the “experts” you encounter are giving you the straight story or using the complexity and media hype as scare tactics.

What is Mold?

Let’s start with the basics: mold is any form of multi-cellular fungi that live on plant or animal (organic) matter. There are more than a million different fungal species in the world. To grow, mold requires food, moisture and time, and can flourish in temperatures between 40 and 100 degrees Fahrenheit. Even in the absence of ideal conditions, mold can lie dormant for years and “re-activate” if living conditions improve.

“Toxic molds,” a term that has been rejected by the American Industrial Hygiene Association and many experts, are those that can produce mycotoxins, and include aspergillus, penicillium, stachybotrys and others. These are the molds that you hear about on television, where some experts say they can cause severe and permanent damage to humans.

How Does it Affect Us?

Health effects of mold are at the heart of the debate. It is agreed that all molds can cause “allergic-type” reactions in humans, such as coughing, wheezing, sneezing, irritated eyes and throat, and runny nose. More severe effects may include flu-like symptoms such as fever, fatigue, respiratory dysfunction, excessive regular nosebleeds, dizziness, headaches, diarrhea, vomiting and impaired or altered immune function. Reports of these more severe symptoms are very rare, and they only occur in a small percentage of the population. Other frightening claims include a loss of balance, cognitive impairment, memory loss, pulmonary hemorrhage, liver damage and near blindness, some of which are claimed to be permanent.

Various scientific groups and agencies are in the midst of research to identify any possible link between mold exposure and permanent damage to humans, but there is no certainty widely agreed upon at this time. Most recently, the American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine published a position statement concluding that current evidence does not support the proposition that human health has been adversely affected by inhaled mycotoxins in home, school or office environments.

There are risks, but we don’t even know how much mold is too much. There are no standards yet for acceptable exposure. There are also no tests for verifying human exposure to mold, in contrast to, for example, lead and asbestos, where physically testing the victim can prove exposure. There is, however, agreement as to who among us is most vulnerable to the effects of mold exposure: infants, children six years and younger, pregnant women, the elderly, asthmatics, allergic individuals and immunecompromised individuals, including those with HIV.

While the health effects are not fully understood, one of the clear dangers of mold for companies in the building industry is the ambiguity due to a lack of definitive standards. The ambiguity is reduced when a genuinely qualified professional assesses a contaminated site and makes recommendations based on professional judgment. But it can get ugly when another party disagrees with that assessment, because the differences in remediation costs can vary wildly and there is often a question of who pays the bills. These differences of opinion occur more often now that attorneys and “Johnny-come-lately” mold experts are an increasingly common part of the equation.

The experts who are brought into a mold case may point to a wide variety of sources for their claims, but the most commonly used guidelines come from the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, hereafter called “NYC,” the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Texas Department of Health and Texas Department of Insurance, the American Industrial Hygiene Association and the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists. The information provided in this article comes from one or more of these sources. To provide some background for companies that may face mold issues, we’ll look at some of the processes used to determine whether mold is a problem, and if so, what needs to be done to address it.

Inspection and Testing

Visual inspection is the most important initial step in assessing a situation. The amount of mold observed determines the extent of the remediation, the level of containment and the type of personal protective equipment required for workers. There are two reasons for the inspection and testing:

➣ To determine the source of the moisture and collect enough information so a repair plan can be developed to make sure the problem does not recur

➣ To determine the extent of contamination so a method of containment and remediation can be developed to safely rid the building of mold.

Bulk or surface sampling is performed by using cellophane tape or a cotton swab to collect the mold. The sample is later analyzed in a laboratory by microscopic (visual) observation. Various authorities note that identification of the spores or colonies requires considerable expertise. The NYC standard maintains that bulk or surface sampling is not required to undertake remediation, and that visual observation is adequate for assessment.

When the quantitative analysis of “how much mold is here” begins, the heart of the difficulty is found: Unlike lead or asbestos, the existence of mold does not have a “yes” or “no” answer. There are always some molds in the indoor environment. We can easily understand that, all things being equal, mold counts in a well-kept home could be less than mold counts of inferior housekeepers. This is just one of the many possible examples of an issue that has nothing to do with building construction, but could be an important variable.

Air sampling is usually performed with the use of a small pump to draw a known volume of air through a collection device that catches mold spores. This sample is analyzed in the lab to determine what types of mold are airborne. It is important to also collect samples of outdoor air to serve as a comparison to the indoor samples. As mentioned previously, there are no standards for determining how much mold is too much, so comparisons to the outdoor and to the non-affected indoor environment are critical to assessing the effects of the building and the environment on the indoor air quality. As you can imagine, the interpretation of this data is inherently complex and problematic, so much so, in fact, that NYC officials say air sampling for fungi should not be part of a routine assessment, since air sampling methods for some fungi are prone to false negative results and cannot be used to rule out contamination. According to the American Industrial Hygiene Association, microbial problems in buildings have shown that perhaps 50 percent of microbial problems are not visible. Thus, destructive testing, such as tearing into the walls to see what is happening, can be warranted, if there is other evidence suggesting hidden problems.

It is my opinion that if enough mold is found to warrant negative air containment or relocation of the occupants, or when an occupant has complained of health susceptibility to mold, an independent Certified Industrial Hygienist or similarly qualified individual should be hired, that is, a professional who is not associated with the business of the contractor performing remediation, and who is paid by or on behalf of the building owner, but not by the contractor. This professional should perform inspections before work begins, write remediation specifications and observe the remediation at defined hold points, including clearance inspections after the work is complete. This serves as a check-and-balance mechanism that experience tells me is always worth the expense.

Many professionals who commonly investigate moisture problems in buildings, including myself, say that projects suffering distress often have many sources contributing to the situation. Be warned that, just because you found a problem, it doesn’t mean you found the problem. Since mold claims often end up in the hands of insurance agents and attorneys, documentation of all observations, conclusions, recommendations and work performed is crucial.

Remediation

For the builder or contractor, remediation means getting rid of mold. There is no definitive authority or standard, and the sources of information are the same as previously noted: NYC, EPA, CDC, AIHA and ACGIH. Some of the information sources refer to the U.S. Department of Labor’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration hazardous work standards, which mandate the level of protection and qualification of workers, and hazard-communication requirements. These OSHA standards traditionally relate to hazardous cleanup for chemicals or asbestos. Another source that is frequently referred to is California’s OSHA and its new sanitation-linked mold requirements (CCR, Title 8 3362).

All authorities on mold stress the importance of repairing the source of the moisture before beginning remediation. A lack of attention to this critical activity may cause many current mold claims to return in the future. If the only professional hired is a CIH or other mold expert, he or she might not know enough about leak and moisture detection and repair to specify and oversee an effective, durable fix. For this reason, it is often necessary to have a building consultant on the team who can find the moisture source, specify a repair and make sure that repairs are performed correctly.

The professional who writes the remediation specification should indicate the level of containment required. Containment means keeping the moldy areas separated from those not affected, and is often accomplished by sealing doors, ducts and other means of escape for contaminated air, or by encapsulating the area with sheet plastic and sealing all of the seams. Most standards call for increasing levels of protection based on the surface area of mold that is found.

The table on p. 83 shows NYC requirements for containment and personal protective equipment. At Level I, no containment is required. Compare this to Level IV, where a complete isolation of the work area from occupied spaces, use of negative air equipment with high-efficiency particulate air filtration, inclusion of air locks and a decontamination chamber in the containment structure are required.

The referenced standards do not take into consideration the hidden mold often found in the course of remediation. When additional mold is found, it is important for the contractor or specifier to re-evaluate the level of protection required.

When containment is required, it is important to notify those who might be affected by the contamination, including building occupants and remediation workers. In the worst of situations, evacuation of buildings might be required. The NYC standards recommend that people who experience adverse health effects associated with exposure to fungal materials should be evacuated immediately from a building undergoing remediation, and they should remain out until the work has been completed. Other criteria for evacuation decisions include the size of the contaminated area, extent of health effects reported by building occupants and the amount of disruption likely to be caused by the remediation activities.

Remediation workers and anyone entering the remediation area may require personal protective equipment based on the corresponding level of contamination. At Level I, workers should wear rubber gloves and wear N- 95-rated masks (less than $5 each). At Level IV, this equipment could include a full-face respirator with twin HEPA-filter cartridges, mold-impervious head and foot coverings and a body suit made of a breathable material, with all gaps, such as those at wrists and ankles, sealed.

Treatment of damaged building components is different for various material types. Nonporous hard surfaces can be wiped clean. Soft materials that suffer contamination, such as wallpaper, wallboard, carpet and padding, are often removed and discarded. Wood framing requires evaluation based on the condition and extent of the mold or deterioration, and the ease or difficulty of replacement. Remediation can require removal of the mold with power tools such as grinders and sanders, then thorough cleaning with scouring pads and HEPA vacuum cleaners.

This is a very labor-intensive process, especially when the workers are wearing “moon suits.” If building contents are analyzed and found contaminated, they need to be meticulously cleaned or discarded. The value of the contents should be considered when making these recommendations, as it is sometimes found that cleaning will cost more than the items are worth.

Not long ago, contractors simply filled the old Hudson sprayer with a mild bleach solution and sprayed away if they found mold. In this use, the bleach solution is technically called a biocide. There are other biocides that were specifically formulated for the same purpose, but most authorities are no longer calling for their use, as repair of the moisture source and removal of the mold will suffice for remediation, and the odors and residual toxicity of biocides is thereby avoided. If there is mold floating around in the air, it stands to reason there might be some in the HVAC system. Guidance on remediation of contaminated HVAC systems is sparse. NYC recommends that the HVAC system be shut down during remediation activities. For Level Vb (see table on p. 83), air monitoring with the HVAC system in operation is recommended prior to re-occupancy. EPA and ACGIH refer to the EPA guide Should You Have the Air Ducts in Your Home Cleaned? The guide suggests having the air ducts in a home cleaned if there is substantial visible mold growth inside hard-surface ducts or on other components of the heating and cooling system. The service provider should agree to clean all components of the system and should be qualified to do so. Improper duct cleaning can cause indoor air problems or damaged ducts.

Clearance Criteria, the standards used for “final inspection” by the mold experts, as you might now expect, have no hard-and-fast rules. AIHA, ACGIH and EPA officials say that a remediation may be judged successful when two criteria are met:

➣ The problem that led to the mold contamination has been fixed

➣ Affected areas have been inspected and visible mold and molddamaged materials have been removed.

If air sampling is performed, the types and concentrations of molds measured indoors should be similar to those measured outdoors or in non-affected areas of the building.

ACGIH researchers add that concentrations of biological agents in any surface samples taken should be similar to those observed in well-maintained buildings or on construction and building finishing materials.

The training and qualifications of contractors and remediation workers is another hazy subject where the authorities refer to existing OSHA standards that deal with toxic cleanup work and hazard communication (again see Cal-OSHA CCR, Title 8, 3362). The OSHA references are mentioned only briefly, probably because there are no national standards specific to mold. These OSHA standards call for workers in heavy contamination areas to be trained to protect themselves and to be fitted with respiratory protection by a trained professional. Unfortunately, the type of “trained professional” is not specified.

Prevention

Given the dangers of mold, the necessity of preventing problems in the first place should be fairly evident. Build it right. But how, you ask? Training is the answer. Sources of information are abundant, but a single source that pulls the information together remains absent. I know of several groups that are trying to help, but they are probably a couple of years from seeing their visions complete, especially for residential construction (see Whole Building Design Guide, www.wbdg.org). For now, start your training program by contacting the National Association of Home Builders Research Center at www.nahbrc.org, reviewing its materials with your staff, making a list of the biggest risks you face, and starting to document and share your company’s best practices with your entire organization. Be sure to save this knowledge base in a structured way so that as new people join the organization, they too can share the accumulated wisdom.

Who needs training? Designers, builders—supervisors as well as workmen—suppliers, manufacturers and all building industry personnel. For window and door industry personnel, good training on proper installation methods and the prevention of problems can begin with ASTM International’s E 2112, the Standard Guide for the Installation of Doors, Windows and Skylights (www.astm.org). The American Architectural Manufacturers Association InstallationMasters training and certification program offers classroom instruction based on the ASTM standard (www.aamanet.org).

Also of interest is the upcoming ASTM standard, Design and Construction of Low-Rise Frame Building Wall Systems To Resist Damage Caused by Intrusion of Water Originating as Precipitation. The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, at www.ashrae.org, also has a wealth of information; you might start with the Handbook of Fundamentals sections on moisture in buildings.

Another aspect of building construction, often overlooked by residential builders, is testing. Assemblies that are not time-tested need to be thoughtfully designed, carefully installed and rigorously tested.

Consumer Education

Finally, education of consumers on what to expect from homes, and how to maintain them is crucial; in fact, it has now been legislated in California. A state Senate bill requires all builders to notify new homeowners of their maintenance obligations in writing. If the builder does not tell the owner that maintenance of an assembly is required, then that assembly had better last past the statute of limitations, or the builder could be on the hook. Owners also need to be taught to keep houses dry, identify leaks immediately and only allow qualified professionals to make repairs. Keeping relative humidity in a home or other building well below 65 percent is important. Builders need to make this easier with the design of the assemblies and training of the owners.

Managing Property Maintenance and Improvement

How to Estimate the Cost of Structural Repairs to Light Frame Construction Required Due to Catastrophic Events

Common Construction Defects