Link to PDF download The DBSKCV™ Construction Management Method by Peter D. Fowler

Publication date: January 1st, 2005

Author: Pete Fowler

What is this DBSKCV TM “Method”

Since the time of the ancient Greeks, humans have been creating and using problem solving "methods" to help us structure situations to aid in identifying the best available alternatives. Some examples of these methods include:

• Classic Problem Solving (Where are we? Where are we going? How do we get there?)

• Scientific Method (Observe, Hypothesize, Predict, Test, Repeat)

• Alcoholics Anonymous' 12-Steps (admit, believe, decide, inventory, confess, prepare, ask, list, amends, continue inventory, pray for knowledge, help)

• Dr. Deming's 14-Points for Quality Management (purpose, philosophy, variation, suppliers, improvement, training, leadership, fear, barriers, slogans, eliminate MBO, workmanship, self-improvement, transformation)

• Six Sigma for Process Improvement (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control)

• Franklin Covey's Project Management Method (Visualize, Plan, Implement, Close)

• Project Management Institute's 9 Project Management Categories (Management of Scope, Time, Cost, Human Resource, Risk, Quality, Procurement, Communication, Integration)

• ASTM Standards: E 2018 Property Condition Assessments, E 2128 Standard Guide for Evaluating Water Leakage of Building Walls, E 1739 Guide for Risk Based Corrective Action.

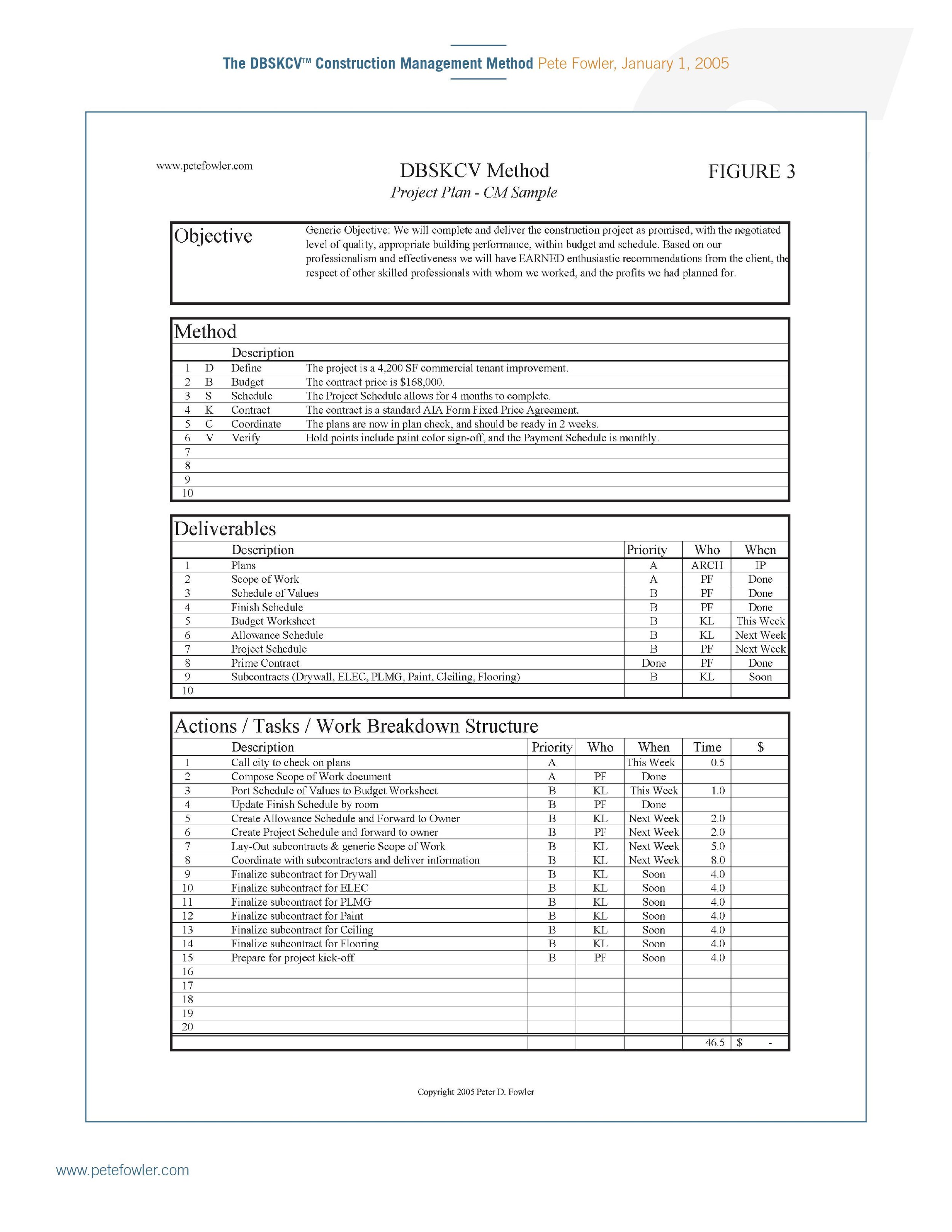

The DBSKCVTM (pronounced "dib-skiv" - DiB-SKCiV) Method is a six-category framework to aid construction professionals in achieving construction project objectives. The DBSKCVTM Method begins with a Project Plan (Figure 1), which starts with identification of the project Objective. We then use the DBSKCVTM Menu of Deliverables (Figure 2) as a menu to select documents or actions that will aid us in moving from where we are to our stated objective. The final step in project planning is to create a step-by-step list of actions. First we plan the work, and then we work the plan. Take a minute or two to review the plan and menu.

This is harder than it sounds. Construction people have a bias toward action; which is a good thing -- we like to see things happen. But we need to resist the temptation to do work before planning. This way, we can be sure to not waste time on unnecessary activity, which is a common source of project failure.

What is Construction Management (CM)?

The Construction Management Association of America (CMAA) says the 120 most common responsibilities of a Construction Manager fall into the following 7 categories: 1. Project Management Planning, 2. Cost Management, 3. Time Management, 4. Quality Management, 5. Contract Administration, 6. Safety Management and 7. CM Professional Practice. This includes specific activities like defining the responsibilities and management structure of the project management team, organizing and leading by implementing project controls, defining roles and responsibilities and developing communication protocols, and identifying elements of project design and construction likely to give rise to disputes and claims.

Why is Construction and Construction Management Important?

Construction professionals are living in a new world. The following social & economic realities make construction, CM and professionalism in construction critical:

• Building construction is a fundamental component of human society.

• Construction constitutes nearly 10% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

• Consumers are expecting quality increases and price decreases in all products.

• The building industry, in general, is not keeping pace with the quality and price improvements that many industries are making.

• The building industry is not attracting the brightest young people into the industry.

• Consumers are more litigious than ever and are becoming more and more so.

• There is a proliferation of attorneys.

• The built-environment has been altered dramatically in the last 20 years.

• Consumers are more conscious of building related health issues than ever.

• In some areas, a lack of skilled construction labor makes the construction professional's job even more critical.

Project Planning and Management

There is no way to 100% guarantee project success. The closest I have found to a guarantee (and I have been looking long and hard) is to hire highly experienced geniuses, or to use a proven system. So if you are not a genius, or can not afford an entire team of them, you better read on.

It is also my experience that planning always saves time. As I mentioned before, construction people want to see things happen and it takes discipline to resist the temptation to start working before completing the Project Plan. Remember: Planning is the closest we can get to a guarantee of project success.

Growing legal risks, administrative issues, sky-rocketing workers' compensation costs, increasing fees and taxation, and complicated insurance issues are only a few of the reasons why the price of construction is higher today than ever before. In addition, managing risk and facilitating a smooth operation are reasons enough to use a system for the management of your project.

We have all heard the adage: "Good people are hard to find." I think good companies are even harder to find. All great businesses create systems that help good people achieve the goals of the company. Most companies, particularly in the construction industry, rely on individuals to develop their own systems. This means the individual has to be some kind of genius. Geniuses are hard to find, but not as hard to find as good companies with good systems.

The construction industry is attracting fewer "geniuses" than other industries. We need to make it easier for construction managers to succeed, giving them tools and techniques to keep promises, balancing the big three (cost, quality, and time), to offer continuously improving value (more quality for less cost and time), and to earn the money they could make in competing industries. Teaching construction managers to plan profitable projects and manage them through fruition is a fundamental that the construction industry is not doing well enough.

Dealing with contractors and subcontractors requires skill, professionalism, and a system. The quality of contractors ranges from excellent to criminally incompetent, which can make the process range from complex but satisfying, to nightmarish and costly. We can not rely on contractors to act professionally – if they do, let it be a pleasant surprise, and when some don't, we must have a system in place to manage the problem. My experience suggests that a nice but incompetent contractor might cost us more than a competent criminal. Don't let yourself be the victim of a contractor's lack of sophistication. If you use a process to guide you in dealing with problem contractors and project pitfalls, success is much more likely. The right planning activities at the beginning of the project will equip you to deal with the incompetent or the unscrupulous.

Summary of the DBSKCV™ Method

• Building construction is a fundamental component of human society.

• Construction constitutes nearly 10% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

• Consumers are expecting quality increases and price decreases in all products.

• The building industry, in general, is not keeping pace with the quality and price improvements that many industries are making.

• The building industry is not attracting the brightest young people into the industry.

• Consumers are more litigious than ever and are

Each of these categories could be books by themselves. The idea here is to fly over the subject of Construction Management so that we see the big-picture. We need to understand the forest, so we don’t get lost in the trees. Dealing with details before understanding the big picture can be dangerous. In construction, dangerous means expensive.

I. Define the Scope of Work

The “Define” phase of construction management consists of documenting the work to be performed. This is usually done graphically and in writing with plans, specifications, references to codes and standards, and detailed “Scope of Work” documents. Getting a clear, specific and detailed project scope is the first step in the construction project management process.

See the DBSKCV™ Method Menu of Deliverables (Figure 2) for the most common scope of work documentation. Depending on the type of project, this is sometimes the work of architects and engineers, but many projects are defined by owners and contractors.

Complete, detailed scope of work documentation allows parties a mutual understanding of what is being bought and sold. My company has consulted on many projects where the owner and the contractor were in dispute and the root cause was a lack of clarity from the beginning. A good “scope of work” is like building on a proper foundation and should identify the quantities and locations (“scope”) of the work as well as materials, specifications, methods and standards of workmanship. Until you have specified in writing the location, size, shape, materials and workmanship you are envisioning for your project, you are not ready to move forward in the planning process. The “scope of work” (i.e. mutual understanding of what is being bought and sold) should be updated as necessary throughout the project.

Keep in mind that the specifications or methods that are defined in the Scope of Work can mean the difference between long term success and failure. As an example, the right paint specifications can double the life of a paint job. If the owner thinks they are buying a 10-year paint job, but the specification will not deliver, a “re-meeting of the minds” might be called for.

Owners or their representatives should not sign a one or two page “Proposal” from a contractor. The “Scope of Work” in such a document is not likely to contain information specific enough to protect the owner if the workmanship is poor. In addition, the contract language will not protect the parties as well as a more complete and professional contract.

II. Budget

Estimating and budgeting are stand-alone areas of professional practice which some construction professionals dedicate their entire careers to. A good estimate for construction is based on lots of assumptions, including the scope of work. If the scope is a moving target, so will the construction costs. Direct costs of construction are usually categorized by Labor, Materials, Equipment and Subcontractors. Most good contractors estimate what they think direct construction costs will be, and then add for overhead, profit, other project costs and contingency, to come up with a contract price.

Total construction cost is made up of so many little pieces that it can become incomprehensible without a system for management. My company has worked on projects in dispute where the records were maintained so poorly that it was impossible to determine the exact costs of construction.

The importance of managing the budget cannot be understated. Before, during and after construction, the construction manager should always know where the project stands relative to the budget. During the course of construction you should know exactly what has been paid and the approximate amount remaining to complete the project.

Keeping an Expense Register that is coded to allocate all expenses is a critical activity so the original and updated Schedule of Values can be compared to the actual project expense. A Budget Worksheet (similar to AIA form G703) should be setup at the beginning of the project and maintained through project close.

III. Schedule

A schedule can take many forms, including Barr / Gantt charts, or CPM (Critical Path Method) Schedules, but the simplest is a list of activities and when they will be performed. A competent contractor should be willing to put a schedule in writing. The owner should add some contingency time of her own. The schedule gives everyone an idea of what will go on and when and will serve as a measuring stick to compare plan to actual progress. With this tool, everyone can identify problems early.

Scheduling is about communication. Successful project management requires communication of expectations with everyone involved: owner(s), designers, contractor(s), government agencies, subcontractors, suppliers, and more. Each activity in construction is usually pretty simple; the greatest difficulty is often in coordination of so many parties. There are often more things to do and coordinate than people can keep organized in their heads. Unfortunately, many projects never have a schedule put to paper, or even if they have one at the beginning, it is not used as a management tool throughout construction.

IV. Contract

A contract is a binding agreement. It should be used as a communication tool to make sure that all parties understand and agree exactly what is being bought and sold. Like any other powerful tool, it can be dangerous, so be careful. Don’t let the excitement of a big project, a smooth talker, or a busy schedule allow you to gloss over the details

A prime construction contract is an agreement between the owner and a contractor. A subcontract is an agreement between a prime contractor and some other contractor who will perform all or a portion of the work covered in the prime contract. Thus, if an owner contracts directly with a “subcontractor” like a painter, this is not a subcontract; it is a prime contract. Prime and subcontractors have different rights and responsibilities. Unfortunately, some prime and sub-contractors do not operate professionally.

All contracts for construction should be in writing. We will hit only the high-points here, but at a minimum, a construction contract should contain:

• Full contact information for all parties to the agreement, including contractor license information, physical location of all parties, and a description of the property in question.

• Detailed “Scope of Work” with material, equipment and workmanship specifications. This might include plans, and written specifications describing the work in detail, a list of fixtures, etc...

• Contract Price (Schedule of Values, Allowance Schedule, etc…)

• Payment Schedule

• Construction Schedule and any consequences for failure.

Change Orders are a natural part of construction and a contingency for them should be built into the budget. Change orders become a part of the construction contract, should always be in writing, and should be negotiated and signed at the time the change occurs, not at the end of the project.

A Payment Schedule should be negotiated at the time the contract is signed. Try to never pay more than the value of the work in place. That is, if the project is 50% complete and you have paid 75% of the contract price, then you are in a dangerous position.

Contractors’ lien rights are a complicated collection of legal protections to make sure contractors get paid for improving property. Collection of lien releases verifies that contractors have been paid and protects the property from liens.

V. Coordinate

The “coordinate” phase of construction management takes our planning and puts it to work. We spend a lot of time and energy in the define, budget, schedule, and contract phases, even though we get none of the satisfaction of seeing physical work take place. Remember: When the time to perform has arrived, the time to prepare has passed. If you effectively defined, budgeted, scheduled, and contracted the project, then this phase will go as smoothly as construction ever goes (so there will still be some problems to solve). Coordination of contractors, subcontractors, materials, equipment, inspections, changes, unforeseen conditions, personalities and forces of nature are always a challenge.

In addition to the real “work” of a construction project, the coordination phase is where the miscommunication, screaming matches, fistfights, litigation and endless frustration often occur; we could also call this phase “Herding Cats”. Managing a project from beginning to end requires a combination of construction knowledge, management skills, political savvy, and patience. While construction is usually a simple assemblage of labor, material, equipment and subcontractors, there are so many moving parts that things regularly can and do go wrong.

Management of construction requires effective communication. Let’s make this as clear as possible: OVER COMMUNICATE, in writing. If you have never read The One Minute Manager, do so before you start your next project; it takes less than 2-hours and will save more than that in the first week. The point is: (1.) Figure out what good performance looks like, communicate and document it in writing, and get agreement that everyone shares your vision (One Minute Goals). (2.) Make sure there are rewards for good performance because we all want to feel good about doing good work (One Minute Praisings), and (3.) have the courage to administer consequences for poor performance (One Minute Reprimands).

You need to have a filing system for your project and religiously document and file the mountain of project information. There are things that should be performed regularly to keep the project progressing. Forms that might be used and/or updated include: Scope of Work, Specifications, Finish Schedule(s), Schedule of Values, Budget, Expense Register, Project Schedule, Change Orders, Purchase Orders, Contacts List, Daily Log (who did what, how long it took, noteworthy conversations, etc…), Correspondence, Safety Meeting Minutes, Accident Reports, Inspection Check-Lists, Municipal inspection information, etc.

VI. Verify

Verifying that the construction is proceeding as planned is critical. This is where we compare our progress to plan. Big problems start small. When we find variations from our plan, we use our documentation system to memorialize them. Remember that property improvement contractors have become the #1 consumer complaint in the U.S.; if you do not want to be a sad statistic, then problems need to be nipped-in-the-bud.

The building department might want to inspect at specified points for life-safety issues. If someone says no permit is required, ask them to put it in writing, or call the municipality. Remember: The building department is not where inspection ends. We have listened to scores of owners bemoaning their fate saying, “Where were the city inspectors?”, when they had buildings that leaked or were otherwise constructed poorly. The owner or representative will want to “verify” at various hold-points to ensure the quantity and quality of workmanship. There may be special assemblies like roofs, decks, windows or weather-resistive assemblies that should be tested to make sure they were constructed appropriately

The contractor will be asking for payments based on the Payment Schedule and you will need to verify the work is complete and built to the standards established in the “define” phase of planning. In addition, the owner will want to collect lien releases for work that is completed and paid.

Conclusion

Remember: 1. Use a system to document your objectives and the process of construction, in writing. 2. Communicate with all of the players in the process. 3. Put everything in writing: People are more committed and more accountable when they have put all their promises in writing.