Understanding the Roles & Responsibilities in Building Projects

Explain It Simply

"If you can't explain it simply, you don't understand it well enough." - Albert Einstein

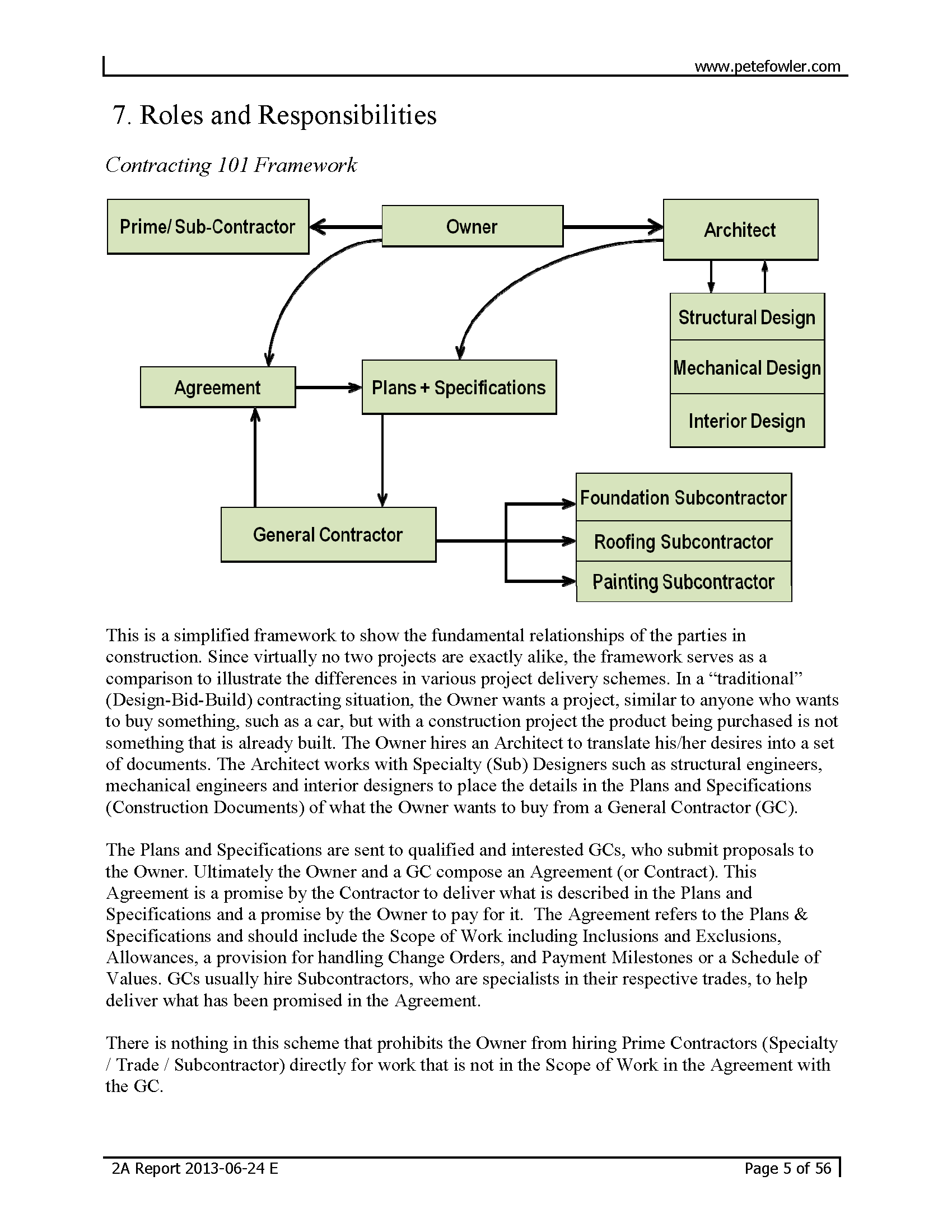

The building industry is terrible at explaining how it does what it does. And this is coming from a guy who has a Bachelor of Science in Construction Management! It’s so bad that I was once working on a construction litigation matter and needed the most basic of organizational charts to explain to a jury the most common roles, relationships, and responsibilities of the various parties involved in a typical construction project; but there was none to be found. I would have loved to have had a reliable source like American Institute of Constructors, The Construction Specifications Institute, the American Institute of Architects, or some similar organization to rely on, to tell my story to the jury. I searched and searched and there was just nothing simple enough to use for a group of people with no construction experience. Everything was overly complex, attempting to account for every possibility. So I locked myself in my office alone one weekend with a pile of flip-chart paper and made iteration after iteration, and finally I nailed it. That was more than a decade ago. Since that time almost every trial or arbitration I have testified in has included some version of this org chart to explain the roles of the parties to one another and to the physical work.

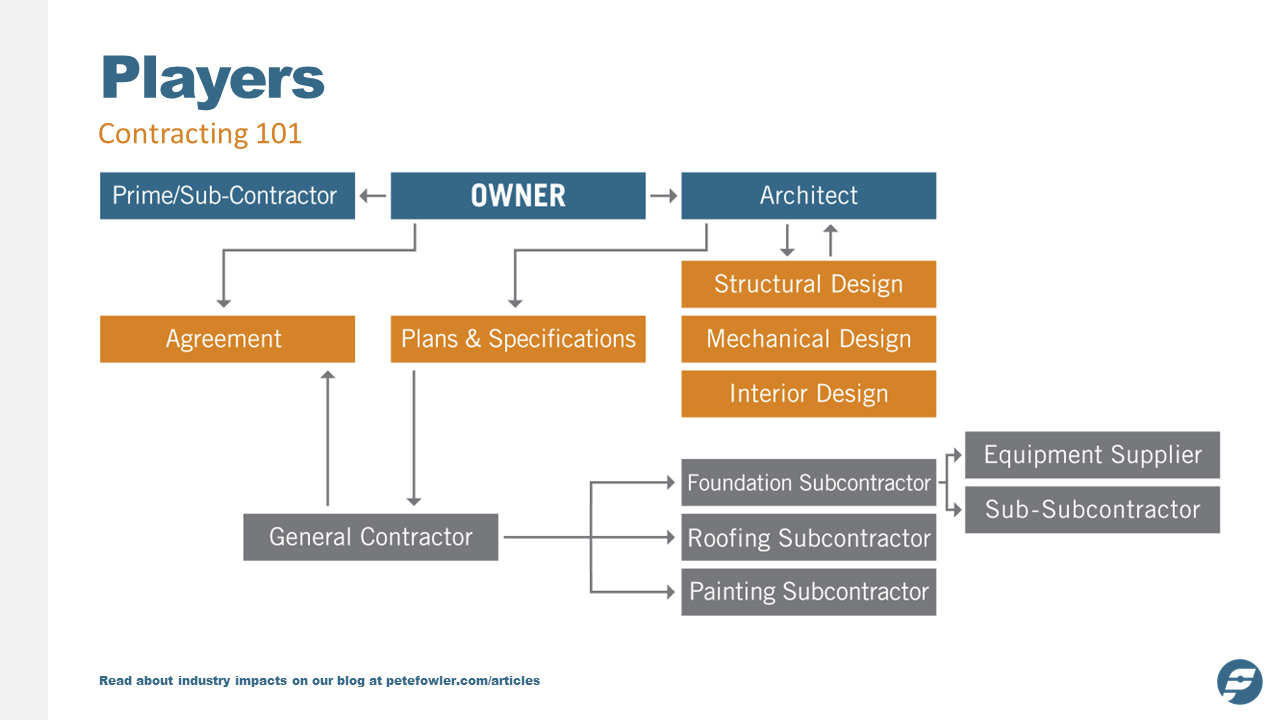

The Contracting 101 Framework

An Owner wants a project, similar to anyone who wants to buy something, such as a car, but with a construction project the product being purchased is not something that is already built.

The Owner goes to an Architect (or in some cases a non-architect designer) to translate his/her desires into a set of documents. This process is intended to “define” what the Owner wants to buy (often from a General Contractor).

The Architect works with Specialty (Sub) Designers such as structural engineers, mechanical engineers and interior designers to further detail the Plans and Specifications (also referred to as Construction Documents) because buildings are so complex that many specialized professionals are required.

The Plans and Specifications are sent to qualified and interested General Contractors, who submit proposals to the Owner. Ultimately the Owner and a General Contractor compose an Agreement (or Contract).

An Agreement for construction is simply a promise by the Contractor to deliver what is described in the Plans, Specifications, and other contract documents, and a promise by the Owner to pay for it.

The Agreement refers to the Plans & Specifications and should include clear definition of the Scope, Budget, and Schedule, including at Scope of Work document that includes: Inclusions and Exclusions, Allowances, a provision for handling Change Orders. The Agreement should include a Schedule of Values and Payment Milestones (for management of the Budget). And finally, the Agreement should include a Progress Schedule.

GCs usually hire specialty trade contractors, commonly referred to as Subcontractors when they are working for a prime (or general) contractor, who are specialists in their respective trades, to help deliver what has been promised in the Agreement. This is, again, because buildings are so complex that many specialized professionals are required.

There is nothing in this scheme that prohibits the Owner from directly hiring Specialty/Trade Contractors (that are called Subcontractors if they are working for a General Contractor) for work that is not in the Scope of Work in the Agreement with the GC. In this situation they are Prime Trade Contractors.

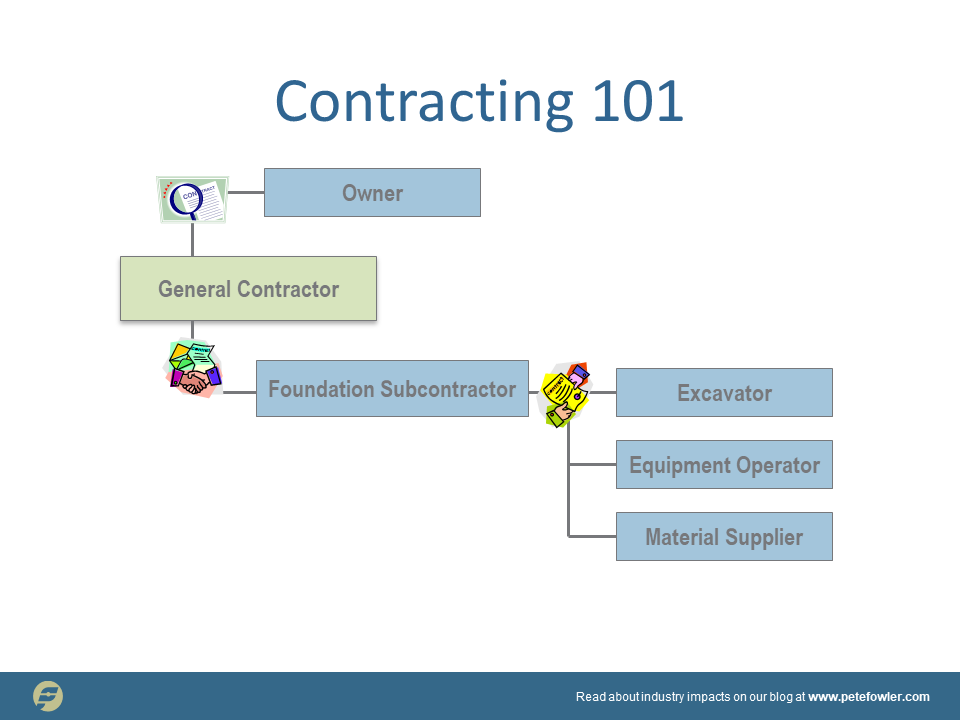

Most of the Subcontractors, and Prime Trade Contractors, have their own suppliers and subcontractors: these are called Sub-Subcontractors. (See diagram below)

Using the Contracting 101 Framework

So the point of the Contracting 101 Framework is to foster understanding of the project at hand. Begin by printing the diagrams above and writing the names of the project players over the generic descriptions. Virtually every project will be different than the Contracting 101 Framework, so you might have to compose multiple iterations, moving the boxes around to fit the peculiarities of your project. I often do this in my office where we have multiple whiteboards and I move back and forth from one to the next until I get my organizational chart to accurately reflect the complexity of the roles and relationships of the current situation. The "compare and contrast," from the simple "Contracting 101 Framework," to the complexity of the real world, is often incredibly instructive.

Sample Project: Custom Single Family Residence

This project was a train wreck.

The Architecture firm and the General Contracting firm were both owned by the same person, but the Owner did not know that (which is unethical and illegal without following strict consent laws). By the time the Owner tried to get control of the project, the two firms had taken $3.5 million dollars to turn a $2.9 million home (initial purchase cost) into a lumber pile. The contract called for distinct design phases but the design was never finished, and it called for the Architect to serve as the Construction Administrator (Owner Representative), but that was a sham since the entities are so closely related and have employees who work for both businesses. The construction work, based on an incomplete design, was executed negligently at inflated prices. The construction work onsite should have been halted long before it was. When the Owners finally asked for a legitimate halt to the construction work, to sort our a plan to go forward, both entities terminated the agreements (using the same lawyer) and engaged in a scorched-earth litigation policy that ensured the maximum economic damage possible from this terrible situation.

Sample Project: Construction Site Accident

Above is a slide from a 2010 trial presentation. This case came precariously close to trial.

The project was a four story 445-unit apartment community. The property Owner was also the developer. The General Contractor entered into a cost-plus prime contract with Owner. The General Contractor entered into an agreement with the Plastering Contractor for $6.5 million. When asked by the General Contractor to perform scaffolding work outside their scope, the Plastering Contractor contracted with a specialty Scaffolding Contractor to furnish a system to access the interior walls of the air shafts at the project. So the key parties included the Owner, General Contractor, Subcontractor (plaster), Sub-Subcontractor (scaffolding), and all of their respective staff.

The injured individual was the crew lead for the Sub-Subcontractor. That day he was part of a three-man crew setting up scaffolding in an air shaft of one of the buildings. The crew was removing the temporary wood flooring previously installed by another subcontractor and the injured employee fell approximately 35 feet to the concrete floor below.

Sample Project: Claim for Nonpayment / Counter Claims for Defects & Delays

This project was the complete renovation of a commercial retail center. The Owner entered into a direct contract with our client, a Paving Company, as well as many other contracts with prime and trade contractors. The Owner had an independent contractor, who was a formerly licensed general contractor, on-site as a supervisor. Our client's initial complaint and mechanics lien were filed to collect $282,400 in work performed. The Owner cross-complained that the work was not completed in the 30-day agreed time limit, that some items were not completed ever, that some work was performed that was outside the contract scope of work (all of which had very sensible explanations).

The primary argument the Owner / Developer was trying to make was that they were NOT playing the role traditionally played by a general contractor or construction manager (which was RIDICULOUS). The Contracting 101 / Roles & Responsibilities Analysis PFCS performed in this matter, particularly the organizational chart above, made their argument seem silly (because it was).

Sample Project: Condominium Conversion

This project arose from construction defect allegations related to the conversion of a 32 unit apartment complex originally built in 1975 into condominiums. The Developer/Converter purchased the 32 unit apartment complex and almost immediately began the conversion to a condominium complex utilizing a Specialty General Contractor (our client) and many other other contractors. Plaintiff alleged that the Specialty General Contractor's scope included defective work. Our client was a general contractor who, according to invoices, performed property maintenance, repair and improvement work related to the conversion including demolition, work in garages, on balconies, stucco, fences/gates, finish carpentry, doors, and electrical totalling $186,165.00.

One of the key allegations was that our client was THE General Contractor, which was not the case. You will see from reading two and a half pages from the 56 page report that our Roles & Responsibilities analysis made clear that the Owner/Developer was in the drivers seat for all important decisions on this project.